When you pick up a generic inhaler, patch, or injection, you expect it to work just like the brand-name version. But how do regulators know it actually does? The answer lies in bioequivalence-a scientific process that proves two drugs deliver the same amount of active ingredient to the right place in the body, at the right speed. For pills, this is straightforward. For complex delivery systems like inhalers, patches, and injections, it’s anything but.

Why Bioequivalence Isn’t the Same for Everything

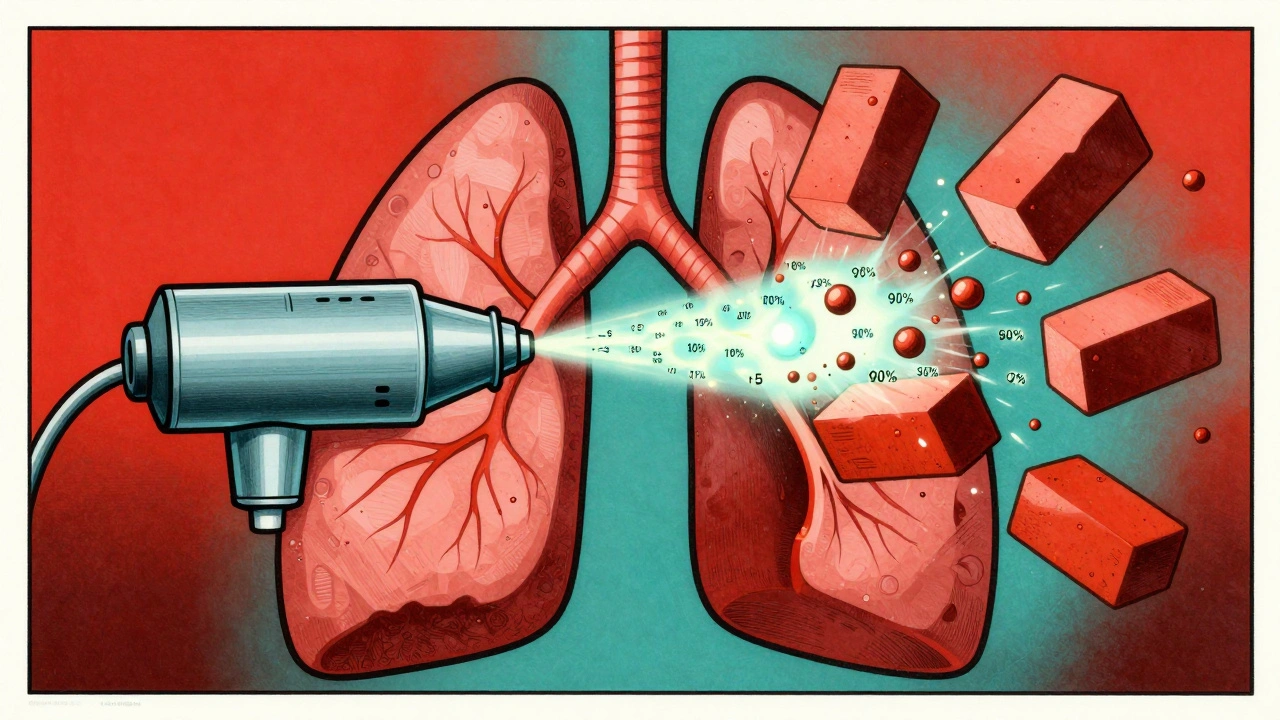

For oral tablets, bioequivalence is measured by tracking drug levels in the blood. If the generic reaches the same peak concentration (Cmax) and total exposure (AUC) as the brand, within 80-125%, it’s approved. Simple. But what if the drug isn’t meant to enter your bloodstream at all? Take inhaled corticosteroids for asthma. The goal isn’t to flood your blood with the drug-it’s to deposit it directly in your lungs. If the particle size is off by a fraction of a micron, or the spray pattern changes slightly, the drug might stick to your throat instead of reaching your airways. That’s not bioequivalence-it’s therapeutic failure. The FDA and EMA know this. That’s why they don’t just rely on blood tests for these products. They demand proof that the drug behaves the same way from the moment it leaves the device.Inhalers: It’s Not Just the Drug, It’s the Device

An inhaler isn’t just a container with medicine. It’s a precision instrument. The FDA’s 2022 guidance says a generic inhaler must match the original in three key ways:- Particle size: At least 90% of the drug particles must be between 1 and 5 micrometers. Too big? They hit your throat. Too small? They get exhaled before reaching the lungs.

- Delivered dose: Each puff must deliver within 75-125% of the labeled amount. No more, no less.

- Plume geometry: The spray’s shape, speed, and temperature must be nearly identical. One company lost approval because their generic albuterol MDI had a plume that was 2°C warmer than the brand-despite identical drug content.

Patches: Slow Release, Big Consequences

Transdermal patches are designed to release drug slowly over hours or days. Nicotine patches, fentanyl patches, estrogen patches-all rely on consistent, controlled delivery. But here’s the problem: blood levels don’t tell the full story. The FDA’s 2011 guidance requires patch manufacturers to prove:- In vitro release: The drug must release at the same rate from the patch as the original, at every time point, within 10%.

- Adhesion: The patch must stick the same way to skin under different conditions-sweat, movement, temperature.

- Residual drug: After use, the leftover drug in the patch must match the original. If the generic leaves more drug behind, it means less was delivered to the body.

Injections: When the Drug Itself Is the Device

Injectables are tricky. For simple solutions like saline or antibiotics, standard bioequivalence works fine. But for complex injectables-liposomes, nanoparticles, long-acting suspensions-it’s a different game. The FDA’s 2018 guidance requires manufacturers to prove:- Physicochemical identity: Particle size must be within 10% of the original. Polydispersity index must be under 0.2. Zeta potential must be within 5mV. If these numbers drift, the drug’s behavior changes.

- In vitro release: The drug must come out of the formulation at the same rate over time.

- Pharmacokinetics: For drugs with a narrow therapeutic window-like enoxaparin (Lovenox)-the bioequivalence range tightens to 90-111% for both Cmax and AUC.

Why This Matters to Patients

You might think, “If the generic is cheaper, why does it matter if it’s not exactly the same?” But here’s the reality: for these delivery systems, small differences aren’t just technical-they’re clinical. A patient using a generic inhaler with slightly larger particles might have more asthma attacks. A patch that doesn’t stick well could lead to opioid withdrawal in chronic pain patients. A faulty injectable could cause dangerous spikes in blood thinners. That’s why regulators don’t cut corners. The cost? High. Developing a generic inhaler can cost $25-40 million and take 3-4 years. Compare that to $5-10 million and 18-24 months for a standard pill. And yet, these complex generics make up only 15% of the generic market by value-even though they’re used in 30% of prescriptions. The trade-off is clear: fewer generic options, but higher confidence that the ones that make it are safe and effective.

Who’s Doing It Right

Some companies have cracked the code. Teva’s generic ProAir RespiClick, approved in 2019, used scintigraphy imaging to prove identical lung deposition. Within 18 months, it captured 12% of the market. How? They didn’t just match the drug-they matched the device’s performance in real human lungs. Other leaders like Mylan and Sandoz have built teams of regulatory scientists, pharmacokinetic modelers, and device engineers to tackle these challenges. The FDA’s Complex Generic Drug Product Development program has helped 42 small companies navigate this path, offering early feedback and technical guidance. The future? More use of physiologically-based pharmacokinetic (PBPK) modeling. In 2022, 65% of complex generic submissions included PBPK simulations-up from 22% in 2018. These computer models predict how the drug behaves in the body based on its physical properties, reducing the need for expensive human trials.The Bottom Line

Bioequivalence for inhalers, patches, and injections isn’t about matching blood levels. It’s about matching performance. The drug, the device, the delivery, the patient’s interaction with it-all must align. This isn’t just regulatory bureaucracy. It’s patient safety. The system isn’t perfect-approval rates are low, costs are high, and some experts call the rules too burdensome. But every rejection, every failed attempt, every additional test? It’s there because someone’s life depends on it. The next time you pick up a generic inhaler or patch, remember: behind that simple label is years of science, millions of dollars, and a relentless focus on making sure what you’re using works exactly as it should.Are generic inhalers as effective as brand-name ones?

Yes-if they’ve passed full bioequivalence testing. Generic inhalers must match the original in particle size, delivered dose, plume pattern, and lung deposition. The FDA has rejected generics that passed standard blood tests but failed to deliver the drug properly to the lungs. Only those that prove identical performance in real-world use are approved.

Why do some generic patches cause skin irritation?

It’s usually not the drug-it’s the adhesive or backing material. Generic patches must match the original’s adhesion, residual drug, and release rate. If the adhesive is too strong or contains different chemicals, it can cause irritation or poor sticking. Regulators require skin compatibility testing, but differences in manufacturing can still lead to minor side effects in sensitive individuals.

Can a generic injection be unsafe even if it’s bioequivalent?

Yes, if the delivery device changes. For auto-injectors like Bydureon BCise, the needle mechanism, plunger force, and timing affect how the drug is released under the skin. Even if the drug concentration is correct, a different injection profile can lead to inconsistent absorption. That’s why regulators now test the entire system-not just the liquid.

Why are generic complex drugs so expensive to develop?

Because they require advanced equipment and multiple layers of testing. Inhalers need cascade impactors ($200K+), patches need Franz diffusion cells ($50K-$100K), and injectables need particle analyzers ($200K+). Each study takes months, and failure means starting over. A single failed batch can cost millions. That’s why only big companies or those with deep pockets usually attempt them.

Is there a risk that multiple generics could make a drug less effective over time?

Yes-this is called "biocreep." Each new generic might be within acceptable limits compared to the original, but small differences can add up. For example, three generations of inhalers, each with a 5% change in particle size, could result in a 15% drop in lung delivery. Regulators are aware and are moving toward stricter standards and long-term monitoring to catch these cumulative effects.

Brian Perry

December 3, 2025 AT 11:47Josh Bilskemper

December 5, 2025 AT 04:38Storz Vonderheide

December 7, 2025 AT 00:05dan koz

December 7, 2025 AT 12:17Kevin Estrada

December 8, 2025 AT 20:05Katey Korzenietz

December 10, 2025 AT 06:33Ethan McIvor

December 11, 2025 AT 14:12Michael Bene

December 13, 2025 AT 06:23Chris Jahmil Ignacio

December 13, 2025 AT 10:24Pamela Mae Ibabao

December 14, 2025 AT 04:50Adrianna Alfano

December 15, 2025 AT 07:51