Child Urinary Incontinence Symptom Checker

Answer the following questions to identify possible causes of your child's incontinence and learn about treatment options.

Possible Causes & Recommendations

When dealing with child urinary incontinence is a condition where kids lose control of their bladder during the day or night, parents often feel confused, embarrassed, or helpless. This guide breaks down why it happens, what works to fix it, and how you can stay calm and supportive while your child learns to manage their bladder.

What Is Childhood Urinary Incontinence?

Incontinence in children isn’t a single disease; it’s a symptom that can stem from several underlying issues. The two main patterns are daytime incontinence (leakage while awake) and nighttime incontinence, commonly called bedwetting or enuresis. Some kids experience both, while others only have one type. Understanding the pattern helps narrow down the cause and choose the right treatment.

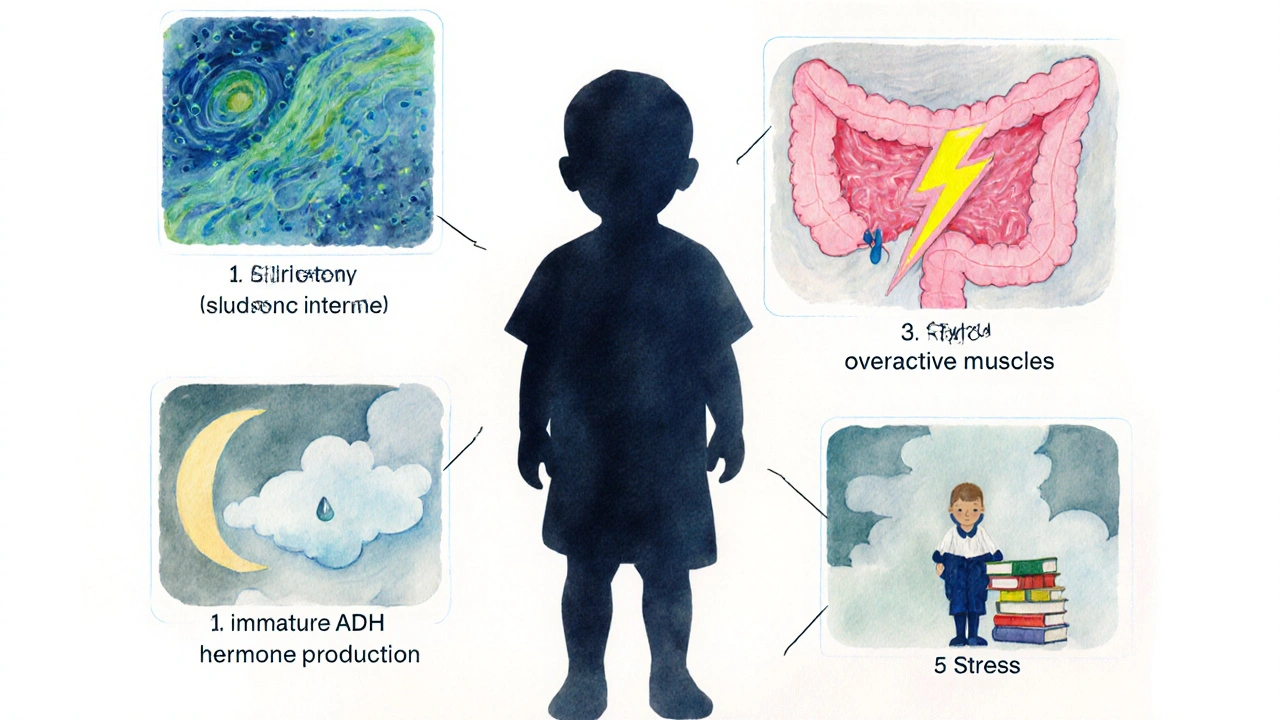

Common Causes to Watch For

Below are the most frequent triggers, each with a quick snapshot of what to look for.

- Urinary tract infection: Burning, frequent trips, or foul‑smelling urine often signal an infection. A simple urine test can confirm it.

- Constipation: A full colon can press on the bladder, reducing its capacity and causing accidents. Look for hard stools or a painful bowel movement.

- Overactive bladder: The bladder contracts too often, leading to urgency and leakage. Children may describe a “need to go right now” feeling.

- Hormonal factors: A hormone called antidiuretic hormone (ADH) isn’t fully mature in younger kids, so they produce more urine at night.

- Stress or anxiety: New school, family changes, or peer pressure can trigger functional incontinence even when the bladder is healthy.

When to Call a Professional

If your child is younger than five, occasional accidents are normal. However, schedule a visit if you notice any of the following:

- Daily daytime leakage after age 7

- Nighttime wetting that persists beyond age 6

- Painful urination, blood in urine, or foul odor

- Sudden change in pattern after a stressful event

A pediatrician can run basic labs and refer you to a pediatric urologist or a specialized continence clinic for deeper evaluation.

Treatment Options Overview

Therapies fall into three broad buckets: behavioral, medication, and devices. The best plan often mixes several approaches.

| Approach | Typical Candidates | How It Works | Pros | Cons |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Behavioral therapy | Most children, especially with mild to moderate symptoms | Bladder training, timed voids, reward charts | No drugs, builds lifelong habits | Requires consistency and patience |

| Medication | Children with overactive bladder or persistent nighttime wetting | Anticholinergic anticholinergic medication relaxes bladder muscle; desmopressin reduces urine production at night | Can produce quick results | Potential side effects, need medical monitoring |

| Device therapy | Kids who respond poorly to other methods | Enuresis alarm sounds at the first sign of moisture, training the brain to wake up | Non‑invasive, long‑term success rates up to 70% | Initial sleep disruption, needs proper placement |

Step‑by‑Step Behavioral Strategies

- Establish a regular voiding schedule: Prompt your child to use the bathroom every 2‑3 hours during the day, even if they say they don’t need to go.

- Teach pelvic floor exercises (also called “Kegels”) in a fun way - pretend they’re “squeezing a tiny balloon.” \n

- Use a simple sticker chart: one sticker per successful dry night or daytime stay dry. Celebrate milestones, but avoid punishments for accidents.

- Limit fluid intake before bedtime to 300ml and encourage a bathroom visit right before sleep.

- Introduce an enuresis alarm if the child still wets at night after 3‑4 months of consistent daytime training.

Medication Insights

Doctors may prescribe an anticholinergic medication such as oxybutynin for children whose bladder muscles over‑contract. Dosage is weight‑based, and side effects can include dry mouth or constipation - monitor closely.

Desmopressin mimics the body’s natural ADH, cutting down nighttime urine volume. It works well for kids with a clear hormonal lag but should be used only under pediatric guidance because of rare water‑balance issues.

Practical Tips for Everyday Life

- Keep spare underwear, pajamas, and cleaning wipes in a discreet “night‑time kit.”

- Teach your child to change bedding quietly to avoid embarrassment.

- Talk to teachers and school nurses early; provide a written plan so they can help with bathroom breaks.

- Stay calm when accidents happen - comment with “It’s okay, we’ll try again tomorrow,” rather than scolding.

- Track patterns in a simple diary: note fluid amount, bathroom trips, and any stressors. This data helps the doctor fine‑tune treatment.

Supporting Your Child Emotionally

Incontinence can affect self‑esteem. Let your child know the condition is medical, not a personal failure. Encourage peer support groups - many hospitals run “dry‑kid clubs” where children share successes.

If anxiety seems high, consider a brief session with a child therapist trained in coping skills. Simple breathing exercises before bedtime can calm the nervous system, which sometimes reduces night‑time episodes.

Frequently Asked Questions

How long does it usually take for a child to stay dry at night?

Most children achieve nighttime dryness within 6‑12 months of consistent bladder training or alarm use. Persistence and keeping the routine steady are key.

Is it safe to use over‑the‑counter laxatives for constipation‑related incontinence?

Short‑term use of a pediatric‑approved stool softener can be helpful, but always get a doctor’s green light. Long‑term reliance may mask the need for diet changes.

Can a child outgrow incontinence without any treatment?

Some kids do outgrow mild nighttime wetting as their nervous system matures. However, proactive treatment speeds up the process and prevents embarrassment.

What should I do if my child refuses to wear an enuresis alarm?

Let them choose the alarm’s color or design, involve them in setting it up, and start with short nighttime trials. Positive reinforcement for each night the alarm stays on helps build acceptance.

When is surgery considered for urinary incontinence?

Surgery is a last‑resort option, usually for severe neurogenic bladder or structural abnormalities that don’t respond to other therapies. A pediatric urologist will assess risk versus benefit.

Jayant Paliwal

October 8, 2025 AT 21:42While the article presents a seemingly comprehensive overview of pediatric urinary incontinence, one must inquire: does it truly interrogate the sociocultural dimensions that underlie parental anxiety?; the guide, though well‑structured, sidesteps the critical discourse on stigma, which perpetuates shame across generations; furthermore, the enumerated treatment modalities, albeit exhaustive, lack a nuanced hierarchy that would aid clinicians in prioritizing interventions; the behavioral strategies, for instance, are described with a naïve optimism that belies the complex neuro‑developmental realities children face; the table of treatment options, while informative, omits a discussion of cost‑effectiveness, an oversight that can jeopardize equitable care; the recommendation to “limit fluid intake before bedtime” is presented without acknowledging the risk of concentrating urine and exacerbating urinary tract infections; the brief mention of dietary adjustments for constipation fails to address the underlying fiber intake deficiencies prevalent in many Western diets; the article’s tone oscillates between prescriptive instruction and casual reassurance, creating a dissonance that may confuse anxious parents; the inclusion of an enuresis alarm is praised, yet the potential for sleep disturbance is glossed over, a point that warrants serious consideration; the section on emotional support, while well‑intentioned, does not provide concrete coping mechanisms beyond generic statements; the absence of a longitudinal follow‑up framework leaves readers without a roadmap for assessing progress over months; the advice to “track patterns in a simple diary” is sound, but the guide does not suggest any digital tools that could streamline data collection; the recommendation hierarchy could have benefited from a decision‑tree graphic, which is conspicuously missing; the article also neglects to discuss comorbidities such as ADHD, which frequently intersect with bladder control issues; finally, the FAQ section, while helpful, repeats information already covered, suggesting a lack of editorial rigor; in sum, the guide is a commendable effort, yet it falls short of the scholarly depth required for a truly authoritative resource.

Kamal ALGhafri

October 9, 2025 AT 19:55In the grand tapestry of child health, urinary incontinence occupies a modest yet symbolically weighty thread; we must remember that bodily functions are not merely mechanical events, but reflections of deeper developmental harmonies; the moral imperative, therefore, lies in treating the child with dignity while addressing the physiological substrate.

Gulam Ahmed Khan

October 10, 2025 AT 18:08Hey, parents! 🌟 Remember that consistency is your greatest ally-set a timer for bathroom breaks and celebrate each dry night with a high‑five or a sticker; the alarm might feel intrusive at first, but it trains the brain to recognize a full bladder, and the results can be amazing; stay upbeat, stay patient, and keep the conversation positive, because confidence fuels progress! 😊

John and Maria Cristina Varano

October 11, 2025 AT 16:22this guide is okay but kinda basic. i think they missed the part about diet. also the tables look messy

Stan Oud

October 12, 2025 AT 14:35Honestly, none of this will help if the child simply refuses to cooperate.

Ryan Moodley

October 13, 2025 AT 12:48One could argue that the entire premise of “behavioral therapy” is a relic of a bygone era, a comforting myth perpetuated by clinicians weary of pharmacological complexities; yet, in a world where data reigns supreme, we must interrogate the evidence base behind timed voiding, for the randomized trials are scant and fraught with methodological loopholes; the article’s endorsement of enuresis alarms, while popular, neglects the systemic review that highlights a 30% dropout rate due to nocturnal disturbance; furthermore, the casual mention of anticholinergic agents glosses over their anticholinergic burden, which can manifest as cognitive fog in a developing brain; the author’s failure to address neurogenic bladder etiologies betrays a narrow focus; nevertheless, the inclusion of a symptom checker is a commendable nod to user‑centric design; while the tone oscillates between clinical and layperson, the lack of rigorous meta‑analysis leaves the discerning reader yearning for depth; in the end, the guide serves as a starter pack rather than a definitive compendium, and that distinction matters immensely.

carol messum

October 14, 2025 AT 11:02It’s interesting how a simple habit like regular bathroom trips can echo larger patterns of self‑regulation in life; small successes build confidence, which in turn fuels further progress.

Jennifer Ramos

October 15, 2025 AT 09:15Great points raised here! I’d add that involving the child in selecting their own reward chart can boost engagement 😊; also, a quick check with the school nurse ensures consistency throughout the day; let’s keep sharing resources and support each other.

Grover Walters

October 16, 2025 AT 07:28From a clinical perspective, the recommendation to monitor fluid intake aligns with standard pediatric guidelines; however, individual variability necessitates personalized assessment, which the article could have emphasized more.

Amy Collins

October 17, 2025 AT 05:42The guide’s KPI on “dry nights” is a classic metric, but without a baseline you’re basically chasing a moving target; also, the pharmacodynamics of desmopressin deserve a deeper dive, given the risk of hyponatremia in pediatric cohorts.

maurice screti

October 18, 2025 AT 03:55When one surveys the extant literature on pediatric enuresis, one is immediately struck by the epistemological chasm that separates anecdotal clinical wisdom from rigorously derived evidence, a fissure that this guide, despite its apparent earnestness, scarcely attempts to bridge; the author’s proclivity for enumerating treatment modalities, while ostensibly exhaustive, betrays an underlying didacticism that privileges quantity over qualitative discernment, a methodological shortcoming that is further compounded by the absence of a systematic appraisal of the relative efficacies of behavioral versus pharmacologic interventions; furthermore, the discourse surrounding the hormonal etiology of nocturnal polyuria is rendered superficial, neglecting the nuanced interplay between antidiuretic hormone secretion patterns and circadian rhythm maturation, a relationship that has been elucidated in recent endocrinological studies; the brief allusion to constipation as a contributory factor, albeit valid, fails to integrate the complex neurogastroenterological feedback loops that modulate bladder capacity via sacral afferent signaling; one must also critique the cursory treatment of psychosocial stressors, which are presented as mere afterthoughts rather than integral components of a biopsychosocial model that contemporary pediatric urology espouses; the recommendation to “track patterns in a simple diary” could be significantly augmented by advocating for validated digital health platforms that employ algorithmic pattern recognition to predict relapse risk; in addition, the guide’s utilization of emotive language, such as “stay calm,” while well‑meaning, inadvertently marginalizes the lived experience of families grappling with chronic incontinence, thereby perpetuating a subtle form of stigma; the omission of cost‑effectiveness analyses for interventions like enuresis alarms versus pharmacotherapy further detracts from the guide’s utility in health‑economically constrained settings; finally, the FAQ section, though comprehensive in scope, suffers from redundancy, reiterating points without offering novel insight, thereby underscoring a need for editorial refinement; in essence, while the manuscript furnishes a valuable scaffold for parents embarking upon the arduous journey of managing child urinary incontinence, it simultaneously beckons for a more scholarly, evidence‑based overhaul that aligns with the highest standards of pediatric practice.

Abigail Adams

October 19, 2025 AT 02:08The article appropriately underscores the necessity of medical evaluation for painful urination, yet it omits a detailed algorithm for urine culture interpretation, which is indispensable for clinicians seeking to differentiate between contaminant growth and true infection; additionally, the recommendation to increase dietary fiber should be accompanied by quantitative guidance, such as recommending 14 grams per 1,000 kcal, to ensure therapeutic adequacy.

Mia Michaelsen

October 20, 2025 AT 00:22While the symptom checker offers a user-friendly interface, it could benefit from incorporating age‑adjusted normative data on bladder capacity, thereby enhancing diagnostic precision for both clinicians and caregivers.

Kat Mudd

October 20, 2025 AT 22:35It is fascinating how the interplay of neurophysiological development and environmental triggers creates a unique profile for each child experiencing incontinence and this complexity demands a compassionate yet systematic approach that balances behavioral interventions with evidence based pharmacology because ignoring either side can lead to suboptimal outcomes and parents often feel overwhelmed when faced with a plethora of options but by breaking down the treatment plan into manageable steps such as establishing a consistent voiding schedule followed by the gradual introduction of an enuresis alarm the process becomes less intimidating and more achievable; moreover the role of diet should not be underestimated and a dietitian can provide tailored recommendations that address both fiber intake and fluid timing which together support bladder health and reduce nocturnal urine production; finally ongoing assessment using a simple diary or a digital tracker allows for timely adjustments and reinforces the child's sense of agency as they see progress unfold which ultimately fosters confidence and long term success

Pradeep kumar

October 21, 2025 AT 20:48Integrating a multidisciplinary team-pediatrician, urologist, dietitian, and behavioral therapist-creates a synergistic framework that addresses the pathophysiological, nutritional, and psychosocial facets of urinary incontinence, thereby maximizing the likelihood of sustained continence.