The Federal Circuit Court doesn’t just hear appeals-it decides when generic drugs can hit the market, how long brand-name drug patents last, and where companies can be sued over drug patents. This single court, based in Washington, D.C., has exclusive power over every patent case in the United States, including the most complex and high-stakes ones in pharmaceuticals. If you’re developing a generic version of a cancer drug, a biosimilar for an autoimmune treatment, or even a new dosing schedule for a common pill, the Federal Circuit is the final word. There’s no other court that can override its rulings on these issues.

Why the Federal Circuit Controls Pharmaceutical Patents

Before 1982, patent cases were scattered across regional appeals courts. A drug patent could be upheld in Texas and thrown out in California. That changed with the Federal Courts Improvement Act, which created the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit and gave it sole authority over all patent appeals. No other circuit court can hear them. That means every pharmaceutical patent lawsuit-whether it’s about a new insulin formulation or a generic version of a blockbuster antidepressant-ends up here.

This isn’t just a procedural quirk. It’s a strategic advantage for patent holders and a major hurdle for generic manufacturers. Because the court has developed deep expertise in patent law, its rulings are consistent-but also rigid. Unlike regional courts that handle everything from divorce to fraud, the Federal Circuit lives and breathes patent law. That specialization means faster, more predictable outcomes, but also less flexibility when it comes to real-world drug development.

The ANDA Game: Filing a Generic Drug Application = Nationwide Lawsuit

Here’s how it works in practice: A generic drug company files an Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA) with the FDA to get approval to sell a cheaper version of a brand-name drug. That’s not just paperwork. Under Federal Circuit precedent, that filing alone creates personal jurisdiction anywhere in the U.S.-even if the company has no offices, warehouses, or employees in that state.

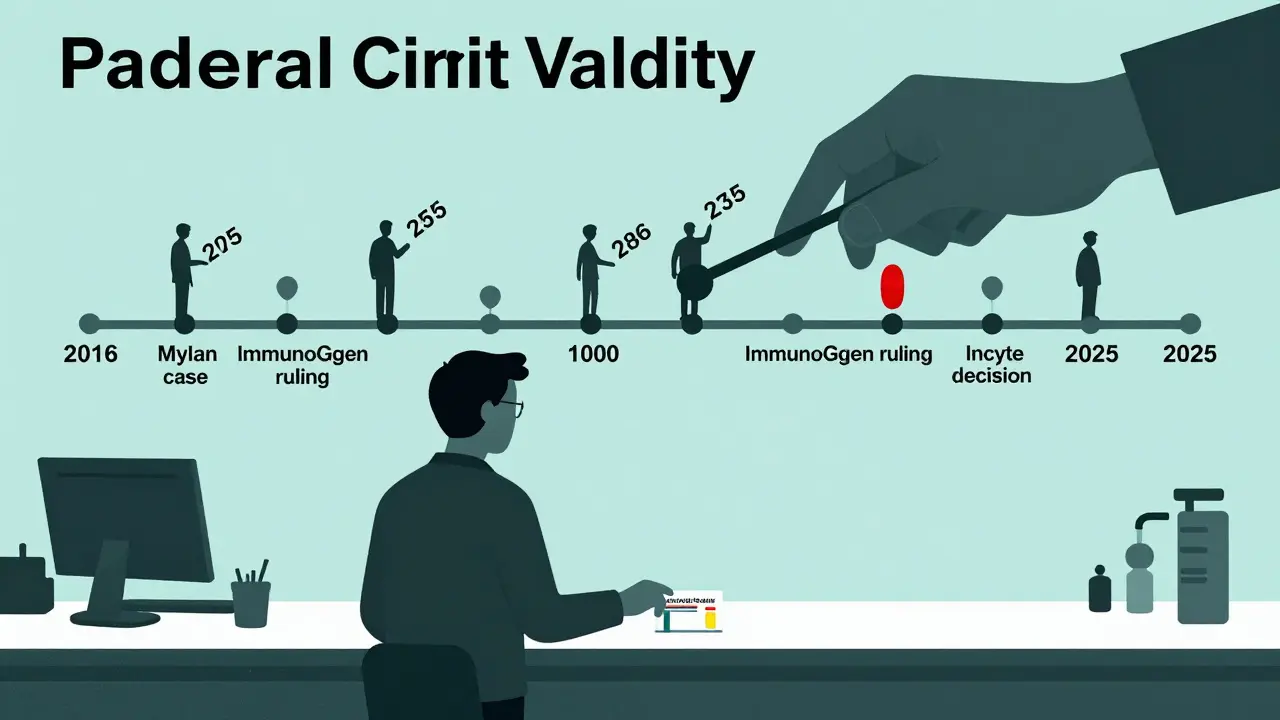

The landmark 2016 Mylan case made this crystal clear. The court ruled that because Mylan applied to sell its generic drug across all 50 states, it had “minimum contacts” with Delaware, a state known for being friendly to patent holders. Since then, over 68% of ANDA lawsuits have been filed in Delaware, up from 42% before the ruling. Brand-name companies now routinely sue in Delaware, knowing they can drag generic makers into court no matter where they’re based.

For generic manufacturers, this means litigation risk is no longer local-it’s nationwide. A single ANDA filing can trigger lawsuits in multiple states, driving up legal costs from an average of $5.2 million to $8.7 million per case between 2016 and 2023.

Orange Book Listings: The Secret Lever That Delays Generics

The FDA’s Orange Book isn’t just a list. It’s the control center for generic drug approval. Every patent listed in the Orange Book can trigger a 30-month stay, blocking the FDA from approving a generic drug-even if the patent is weak or questionable.

In December 2024, the Federal Circuit clarified a critical rule in Teva v. Amneal: a patent can only be listed in the Orange Book if it actually claims the specific drug being submitted for approval. That means if a patent covers a drug formulation, but the generic company is applying for a different version, the patent can’t be used to delay approval.

This decision forced big pharma to be more precise with their patent portfolios. Companies now spend an extra 17 business days on average reviewing each patent before listing it, making sure it matches the drug exactly. It’s a small change-but one that’s already helped clear the path for some generics that were stuck for years.

Dosing Patents: Why Minor Changes Don’t Count Anymore

One of the biggest battlegrounds in pharmaceutical patents is dosing. Can you patent a new way to take a drug? Like taking it once a day instead of three times? Or using a lower dose to reduce side effects?

Before April 2025, companies often got patents for these tweaks. But the Federal Circuit’s decision in ImmunoGen v. the Patent Office changed everything. The court ruled that if the drug itself is already known, changing the dose alone doesn’t make it patentable unless there’s a surprising, unexpected result.

Judge Lourie put it plainly: “Because both sides admitted that the use of IMGN853 to treat cancer was known in the prior art, the only question to resolve was whether the dosing limitation itself was obvious.”

That’s a big deal. A 2024 Clarivate analysis showed pharmaceutical companies cut back on dosing-related patent filings by 37% after this ruling. Instead of chasing weak secondary patents, they’re investing more in entirely new compounds. The court’s message is clear: incremental changes won’t cut it anymore.

Standing: Can You Sue Before You Even Start?

Here’s a twist: you can’t just challenge a patent because you think it’s unfair. You need legal standing. That means you have to show you’re actively developing a product that might infringe it.

In May 2025, the Federal Circuit ruled in Incyte v. Sun Pharma that vague intentions or early-stage research aren’t enough. You need concrete evidence: Phase I clinical trial data, manufacturing plans, or signed supply agreements. This raised the bar for generic companies trying to knock out patents before spending millions on development.

Patent attorneys now advise clients to document every step of development-from lab notes to investor meetings-just to prove they have standing. Judge Hughes, in his concurrence, warned that this standard might be “stifling generic competition,” especially in complex biologics. His concern is now being heard in Congress, where lawmakers are drafting the Patent Quality Act of 2025 to fix this loophole.

How This Affects Real Patients and Drug Prices

Behind every legal ruling is a patient waiting for a cheaper drug. The Federal Circuit’s decisions directly impact how long brand-name drugs hold a monopoly. In 2023, 12 out of 31 pharmaceutical patent cases saw the court reverse lower court rulings in favor of patent holders-far higher than the 22% reversal rate across all patent cases.

That means more delays. More exclusivity. More money spent on drugs that could be generics. The court’s strict rules on dosing patents and standing have slowed the entry of generics into markets for cancer drugs, autoimmune treatments, and even diabetes medications. At the same time, the clarity on Orange Book rules and jurisdiction has helped some generics move faster-once they clear the legal hurdles.

It’s a system designed to protect innovation, but it’s also designed to protect profits. The $380 billion U.S. prescription drug market moves on the outcome of these cases. When the Federal Circuit says a patent is invalid, a generic drug can launch months or years earlier. When it says the patent stands, patients wait-and pay more.

What Comes Next?

The court is still evolving. Its 2025 rulings on biosimilars and expired patents show it’s extending its logic to newer drug types. The Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act, once a gray area, is now firmly under its control. The court is also tightening the rules on patent validity after expiration, making it harder to drag out litigation with expired patents.

Industry analysts predict a 15-20% drop in “evergreening” strategies by 2027-where companies file multiple weak patents to extend market exclusivity. Core compound patents are still strong, with an 82% affirmance rate. But the days of patenting minor dose changes are fading.

The Federal Circuit isn’t perfect. Critics call it insular. Supporters say it brings needed clarity. But one thing is certain: if you’re in the pharmaceutical industry, you don’t just need a science degree-you need to understand this court. Its rulings aren’t just legal opinions. They’re market signals. They’re pricing triggers. They’re timelines on when a life-saving drug becomes affordable.

What makes the Federal Circuit different from other U.S. courts?

The Federal Circuit is the only appellate court in the U.S. with exclusive jurisdiction over all patent cases, including pharmaceutical patents. Other courts handle a mix of civil, criminal, and administrative appeals, but the Federal Circuit only hears patent appeals. This specialization means its judges develop deep expertise in patent law, leading to more consistent rulings-but also less adaptability to real-world drug development needs.

Can a generic drug company be sued in any state after filing an ANDA?

Yes. Since the 2016 Mylan decision, filing an ANDA with the FDA is treated as an intent to market the drug nationwide. That creates personal jurisdiction in any U.S. district court, even if the company has no physical presence there. This is why over two-thirds of ANDA lawsuits are now filed in Delaware, a state known for its favorable patent laws.

Why are dosing regimen patents harder to get now?

After the April 2025 ImmunoGen decision, the Federal Circuit ruled that changing the dose of a known drug isn’t enough for a patent unless there’s a surprising, unexpected result. If the drug’s use is already known in prior art, the dosing limitation alone doesn’t make the invention non-obvious. This has led to a 37% drop in secondary dosing patents filed by pharmaceutical companies.

What is the Orange Book, and why does it matter?

The Orange Book is the FDA’s official list of approved drug products and their associated patents. Listing a patent here can block generic approval for up to 30 months. But the Federal Circuit ruled in December 2024 that only patents that actually claim the specific drug in the application can be listed. This prevents companies from listing irrelevant patents to delay competition.

Do you need clinical trial data to challenge a pharmaceutical patent?

Yes. The May 2025 Incyte decision requires companies to show concrete development activities-like Phase I clinical trials, manufacturing plans, or signed agreements-to prove they have legal standing to challenge a patent. Vague intentions or early-stage research aren’t enough. This has made it harder for startups and smaller generic firms to initiate patent challenges without significant investment.

Virginia Seitz

December 17, 2025 AT 11:24So basically, if you’re a generic drug company, you’re playing chess on a board where the rules keep changing and the opponent writes them? 😅

Meghan O'Shaughnessy

December 18, 2025 AT 22:03I’ve seen this play out in my brother’s pharma job. The Orange Book thing used to be a total mess-now at least there’s some clarity. Still, the cost of litigation is insane.

Erik J

December 20, 2025 AT 16:29Does anyone know if the Federal Circuit ever consults actual pharmacists or clinicians when ruling on dosing patents? Or is it all lawyers and patent examiners debating semantics?

Salome Perez

December 20, 2025 AT 16:44The Federal Circuit’s specialization is both its strength and its blind spot. While consistency in patent interpretation is valuable, the court’s insulation from broader medical and public health contexts creates a dangerous disconnect. When judges treat a 30-month FDA delay as a mere procedural hurdle, they forget that real people are waiting for insulin, antidepressants, or cancer drugs. The law doesn’t exist in a vacuum-it lives in the gaps between prescription bottles and bank accounts.

What’s more, the Mylan jurisdictional expansion effectively turned Delaware into a patent litigation theme park, where corporations litigate not because it’s fair, but because it’s convenient. This isn’t justice-it’s forum shopping on steroids.

And the dosing patent ruling? Long overdue. Evergreening through trivial modifications has been a grotesque abuse of the patent system for decades. It’s time we stop rewarding incrementalism and start rewarding innovation.

But let’s be honest: the court isn’t the villain here. It’s merely enforcing the rules Congress wrote. The real failure lies in legislative inertia. Until we reform the Patent Act to explicitly limit Orange Book listings and require actual therapeutic novelty for dosing claims, we’re just rearranging deck chairs on the Titanic.

Patients don’t need more legal complexity. They need affordable medicine. And right now, the system is rigged to deny them both.

Sam Clark

December 21, 2025 AT 19:03While the Federal Circuit’s rulings have created a more predictable legal environment for patent holders, the unintended consequences on generic market entry cannot be understated. The increased litigation costs, jurisdictional overreach, and heightened standing requirements disproportionately impact smaller manufacturers who lack the resources to engage in multi-state litigation. This dynamic, while legally defensible, undermines the foundational purpose of the Hatch-Waxman Act: to balance innovation with accessibility. A recalibration of jurisdictional standards and a clearer definition of ‘unexpected result’ in dosing patents may be necessary to restore equilibrium.

Evelyn Vélez Mejía

December 23, 2025 AT 00:37Let’s cut through the legal jargon: this court is a cartel enforcer. It doesn’t ‘protect innovation’-it protects monopolies. The fact that a company can file an ANDA in Ohio and get sued in Delaware, where the judge has a history of siding with Big Pharma, isn’t justice-it’s extortion. And the Orange Book manipulation? That’s not patent law, that’s corporate sabotage dressed in legalese.

The ‘unexpected result’ standard for dosing patents is laughable. If you change the dose to reduce toxicity or improve compliance, that’s a clinical advancement. It’s not ‘obvious’ to patients who can’t swallow six pills a day. The court doesn’t live in the real world-it lives in a boardroom with a law degree.

And don’t get me started on standing. You need Phase I trials to challenge a patent? That’s like requiring someone to build a house before they can sue the builder for using rotten wood. It’s designed to silence dissent, not uphold the law.

This isn’t about patents. It’s about power. And until Congress or the Supreme Court steps in, patients will keep paying the price.

Victoria Rogers

December 24, 2025 AT 20:25so like... the feds let one court decide everything? lol. we need to break up the fed circuit. this is why meds cost 10x here vs canada. its all just patent trolling with robes.

delaware? why not just make it a state where all lawsuits go? why not just give it to the patent office? this is so dumb. generic companies are getting crushed and no one cares. #pharmabosses

Naomi Lopez

December 25, 2025 AT 00:50It’s fascinating how the Federal Circuit, through its jurisprudential rigor, has effectively transformed patent law into a high-stakes economic instrument rather than a mechanism for incentivizing innovation. The Mylan decision, while technically sound under Article III jurisprudence, reveals a troubling conflation of commercial intent with legal presence-a doctrinal sleight of hand that privileges corporate convenience over territorial sovereignty.

Moreover, the narrowing of Orange Book eligibility, while a welcome corrective, merely scratches the surface of a deeper pathology: the systemic overpatenting of marginal variations. The ImmunoGen ruling, though laudable, should have been accompanied by retroactive invalidation of thousands of dosing patents-yet the court, ever cautious, opted for prospective application only.

And the standing requirement? A masterstroke of regulatory capture. By demanding clinical trial data to challenge a patent, the court effectively outsources patent validity to the market’s capital allocation, ensuring that only well-funded entities can even enter the arena. This isn’t legal clarity-it’s economic gatekeeping.

The irony is palpable: a court created to unify patent law has instead entrenched a system where access to medicine is determined not by scientific merit, but by litigation budgets.