Fentanyl Patch Overdose Symptom Checker

Identify Overdose Symptoms

Check all symptoms you're experiencing or observing in someone else. This tool helps determine if an immediate overdose response is needed.

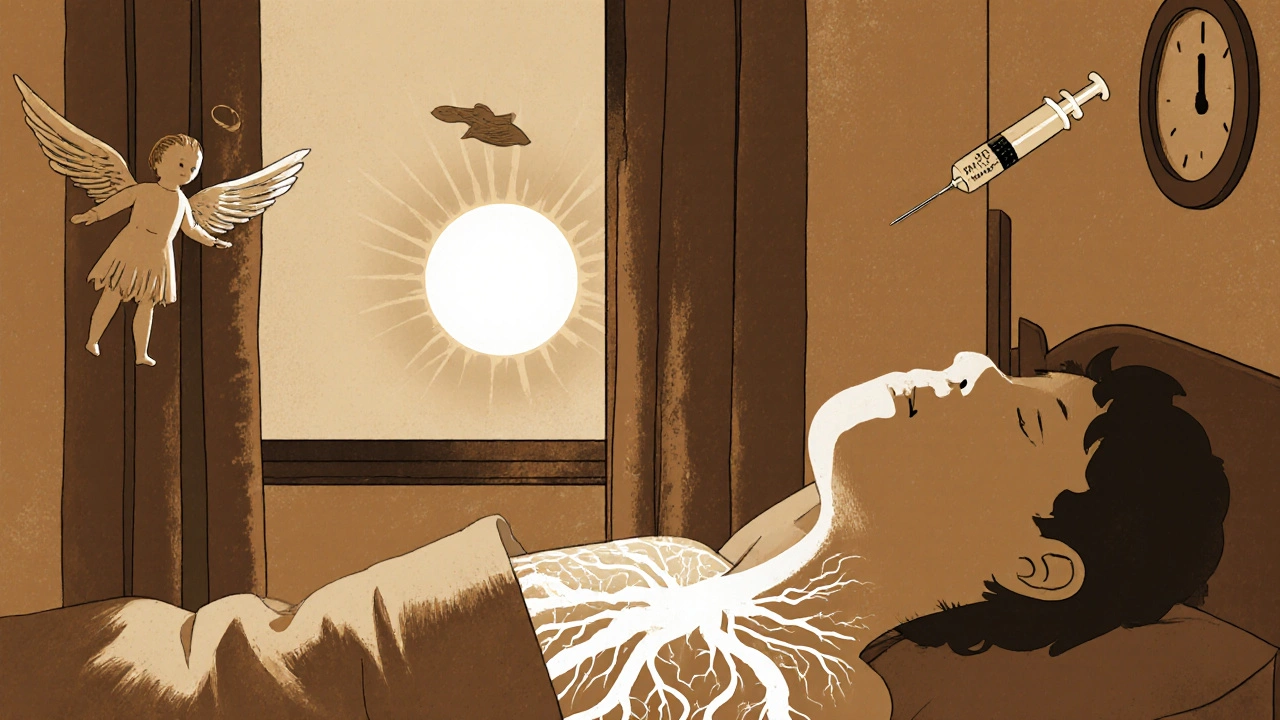

When you're living with severe, long-term pain, a fentanyl patch might seem like a simple solution. It’s applied once every three days, delivers steady pain relief, and avoids the need to swallow pills multiple times a day. But behind that quiet, adhesive patch is a drug fentanyl that’s 50 to 100 times stronger than morphine. And when things go wrong - whether from misuse, accidental exposure, or sudden discontinuation - the consequences can be deadly.

How Fentanyl Patches Work - and Why They’re Dangerous

Fentanyl patches are designed for people who are already tolerant to opioids and need continuous pain control. They’re not for occasional pain, surgery recovery, or first-time opioid users. The patch slowly releases fentanyl through the skin over 72 hours, keeping blood levels steady. That’s good for pain control, but it’s also what makes it so risky. Unlike oral opioids that peak and fade, fentanyl builds up in your system over time. If you’re not used to opioids, even one patch can shut down your breathing. That’s why the FDA and EMA both warn: never use fentanyl patches if you’re not already taking daily opioid pain medicine. The same goes for children. Between 1997 and 2012, 32 children died after finding and sticking on discarded or unused patches. One patch can kill a child.Overdose: The Silent Killer

An overdose from a fentanyl patch doesn’t always look like a drug emergency. There’s no screaming, no collapse. It’s quiet. You might notice someone is unusually sleepy, hard to wake up, or breathing very slowly - so slowly they’re barely moving. Their skin turns cold and clammy. Their lips or fingernails may turn blue. Their pupils shrink to pinpoints. These are the signs the FDA and Mayo Clinic list as clear red flags:- Slow, shallow, or stopped breathing

- Unresponsiveness - you can’t wake them up

- Cold, pale, or bluish skin

- Extreme drowsiness or confusion

- Slow heartbeat or low blood pressure

Withdrawal: When Stopping Isn’t Easy

If you’ve been on fentanyl patches for more than a few weeks, your body has adapted. Stopping suddenly doesn’t just mean your pain comes back - it triggers a full-body shock. Withdrawal symptoms start within 8 to 24 hours after your last patch. They peak around day 2 to 3 and can last up to two weeks. The EMA and American Addiction Centers describe them as:- Intense anxiety and restlessness

- Profuse sweating, chills, and goosebumps

- Runny nose, watery eyes, yawning

- Nausea, vomiting, diarrhea

- Severe muscle aches and cramps

- Insomnia and tremors

- Rapid heartbeat and high blood pressure

- Thoughts of suicide

The Only Safe Way to Stop

You don’t quit fentanyl patches cold turkey. You taper. The EMA and Mayo Clinic agree: reduce the dose slowly. For someone on a high dose (like 100 mcg/hour), that might mean cutting back by 10-25% every 1 to 3 weeks. For some, tapering takes months. Rushing it increases the risk of relapse, severe pain, and overdose. Why? Because after stopping, your tolerance drops. If you go back to using even a small amount of fentanyl - whether from a patch, pills, or street drugs - you’re at higher risk of overdose than ever before. A 2021 Johns Hopkins study found that 37% of fatal fentanyl overdoses happened in people who had recently stopped using. Your doctor should create a personalized taper plan. Never adjust your dose on your own. If you feel like you can’t handle the pain or withdrawal, talk to your provider. There are alternatives: nerve blocks, physical therapy, non-opioid medications, or even switching to a different opioid with a safer profile.What You Must Do Every Day

If you’re prescribed a fentanyl patch, these aren’t suggestions - they’re survival rules:- Never use heat - no hot tubs, saunas, heating pads, or sunbathing while wearing the patch.

- Store patches safely - locked up, out of reach of kids, pets, or visitors. Used patches still contain 80% of the drug. Fold them sticky-side together before throwing them away.

- Don’t share or trade - even one patch can kill someone who isn’t opioid-tolerant.

- Carry naloxone - and make sure someone in your household knows how to use it.

- See your doctor regularly - prescriptions aren’t refillable. You must have check-ins to renew.

- Tell every doctor and dentist - before any surgery, dental work, or new medication. Fentanyl interacts dangerously with benzodiazepines, alcohol, sleep aids, and other opioids.

Why Are Prescriptions Dropping?

Fentanyl patch prescriptions in the U.S. fell 42% between 2016 and 2022. Why? Because doctors are learning the hard way. The CDC now says fentanyl patches should only be used after other pain treatments fail - and only for patients already taking at least 60 mg of morphine daily. The American Medical Association found that 78% of physicians now consider fentanyl patches a last resort, up from 52% in 2016. The FDA’s Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS) now requires prescribers to complete training before writing these prescriptions. Patient education is mandatory. And with naloxone co-prescribing now standard, the system is slowly getting safer.What’s Next?

Researchers are working on safer versions. Two clinical trials are testing new patches that release fentanyl only under strict conditions - like only when skin temperature is normal, or that deactivate if tampered with. But until those are approved, the old rules still apply: respect the power of this drug. Fentanyl patches can help people live with chronic pain. But they’re not a casual tool. They’re a high-risk medical device. Used right, they offer relief. Used wrong, they can end a life - yours, or someone else’s.Can a fentanyl patch kill you even if you’ve been using it for a while?

Yes. Even long-term users can overdose if they’re exposed to heat, take other drugs like benzodiazepines or alcohol, or accidentally apply more than one patch. The drug builds up over time, and your tolerance can change. Never assume you’re "safe" just because you’ve used it before.

What should I do if my child touches a used fentanyl patch?

Remove the patch immediately. Wash the skin with plain water - don’t use soap or alcohol. Call 911 or your local poison control center right away. Even a small amount of fentanyl from a used patch can be fatal to a child. Keep all patches locked up and folded sticky-side together after removal.

Can I drink alcohol while using a fentanyl patch?

No. Alcohol combined with fentanyl can slow your breathing to a dangerous level - even if you’ve used both before. The FDA warns that mixing opioids with alcohol increases overdose risk by up to 10 times. Avoid alcohol completely while using the patch.

How long does fentanyl stay in your system after stopping the patch?

Fentanyl can remain detectable in your body for up to 3 days after removing the last patch, but its effects on your nervous system last longer. Withdrawal symptoms can start within hours and last weeks. Your body’s tolerance drops quickly, so don’t assume you can use opioids again safely after stopping.

Is it safe to cut a fentanyl patch to lower the dose?

Never cut, puncture, or alter a fentanyl patch. The drug is stored in a gel or matrix that releases slowly. Cutting it can cause a sudden flood of fentanyl into your skin, leading to overdose. Only use patches in the exact strength your doctor prescribes.

What if I miss a patch change?

If you forget to change your patch on schedule, put on a new one as soon as you remember. Don’t double up to make up for it. If you’re more than 24 hours late, contact your doctor - you may need a temporary adjustment to avoid withdrawal or overdose. Never skip doses without talking to your provider.

Can fentanyl patches cause addiction?

Yes. Even when taken exactly as prescribed, fentanyl patches can lead to physical dependence. Addiction - where you crave the drug despite harm - is less common in patients using it for pain, but still possible. That’s why doctors monitor usage closely and avoid prescribing them unless absolutely necessary.

Are there safer alternatives to fentanyl patches for chronic pain?

Yes. Many patients find relief with non-opioid medications like gabapentin, duloxetine, or NSAIDs, combined with physical therapy, nerve blocks, or cognitive behavioral therapy. Some use lower-risk opioids like buprenorphine patches, which have a ceiling effect that reduces overdose risk. Always discuss alternatives with your doctor before starting fentanyl.

Ryan Airey

November 15, 2025 AT 20:39Let’s be real - fentanyl patches are just government-approved slow-motion suicide for people who can’t handle their pain or their choices. Doctors hand these out like candy and then act shocked when someone dies. The FDA’s ‘warnings’ are just legal cover. You think they care? They’re making bank off the opioid crisis while families bury their kids. This isn’t medicine - it’s institutionalized neglect wrapped in a patch.

Chris Bryan

November 16, 2025 AT 19:06They say ‘don’t use heat’ but who’s really to blame? The people who leave patches lying around like trash or the system that lets addicts walk out with enough fentanyl to kill a horse? I’ve seen it - grandma’s patch on the bathroom floor, kid picks it up, boom. No one’s checking the homes. No one’s auditing prescriptions. This isn’t about safety - it’s about control. And we’re all just pawns in the pharma game.

Shyamal Spadoni

November 18, 2025 AT 00:48you know what i think? this whole fentanyl thing is just another way for the deep state to control the population through pain. think about it - they make you dependent on something that can kill you in seconds, then they tell you to carry naloxone like its a magic bullet. but who really controls the supply? who decides who gets a patch and who gets locked up? the same people who sold you the painkillers in the first place. its all connected. the military-industrial complex, big pharma, the FDA - theyre all one big machine. and you think you're managing pain? no. you're just another node in the surveillance grid. i mean, have you ever noticed how every time someone overdoses, the news just says 'accidental' and moves on? no real investigation. no accountability. just silence. and thats exactly how they want it. also, i typed this on my phone so sorry for the typos. my hands are shaky from withdrawal. but hey, at least i'm awake right? 😅

Hollis Hollywood

November 19, 2025 AT 05:35I’ve been on these patches for 8 years. I didn’t choose this life - chronic nerve damage from a car wreck did. I get the fear. I get the warnings. I fold my used patches sticky-side in, keep them locked in a safe, and my wife knows where the Narcan is. But let me tell you something - the real horror isn’t the patch. It’s the loneliness. It’s the way your friends slowly stop asking if you’re ‘feeling better.’ It’s the doctors who treat you like a suspect instead of a patient. I’ve cried in waiting rooms because they wouldn’t refill my script without a ‘pain diary’ and three forms signed by three different specialists. I’m not addicted. I’m surviving. And if you’ve never had a spine that screams every second of every day, don’t pretend you know what ‘safe’ looks like for me. I’m not a statistic. I’m a person who still wakes up and tries.

Aidan McCord-Amasis

November 20, 2025 AT 19:52Just don’t use heat. That’s it. 🤷♂️🔥

BABA SABKA

November 21, 2025 AT 12:20the systemic failure here isn't the patch - it's the medical industrial complex's inability to treat pain as a biological reality rather than a moral failing. fentanyl patches are a pharmacokinetic marvel - precise, sustained delivery, bioavailability optimized through transdermal kinetics. but when your provider is overworked, underpaid, and drowning in regulatory paperwork, they default to prescription-as-transaction. no holistic assessment, no behavioral integration, no follow-up. the result? patients become pharmacological ghosts - existing in the liminal space between relief and ruin. the real innovation isn't in safer patches - it's in re-engineering care delivery. we need pain specialists embedded in primary care, not siloed in clinics that charge $800 for a 15-minute consult. until then, we're just rearranging deck chairs on the titanic while people drown in opioid-induced respiratory depression.

Jonathan Dobey

November 22, 2025 AT 15:32Oh, the irony. We’ve turned human suffering into a bioengineered commodity, then wrapped it in a plastic-backed adhesive that whispers death with every passing hour. Fentanyl - the silent symphony of the pharmaceutical age. A molecule so potent it bends the laws of biology to the will of profit margins. We call it medicine, but it’s more like a Faustian bargain written in Latin and signed with a barcode. The FDA’s ‘risk mitigation’? A performative ritual. A theater of control. Meanwhile, the real tragedy isn’t the overdose - it’s the quiet desperation of the millions who’ve been taught that their pain is too great for anything but chemical surrender. And yet… here we are. Still breathing. Still patching ourselves together. Still hoping the next dose doesn’t become the last.

ASHISH TURAN

November 23, 2025 AT 19:02My uncle died from a fentanyl patch he found in his trash. He wasn’t even on opioids. Just a retired teacher who didn’t know how to dispose of it. I’ve seen what happens when education fails. The government gives you a patch but doesn’t teach you how to handle it. That’s not negligence - that’s betrayal. Please, if you’re prescribed this, teach your family. Show them how to fold the patch. Show them where the naloxone is. Don’t wait until it’s too late. Your life isn’t just yours - it’s everyone who loves you.

Ogonna Igbo

November 24, 2025 AT 11:26Listen here you all talk about safety and warnings like this is America or Europe. In Nigeria we don't have fentanyl patches because we don't have the system to support them. We have people in villages with broken bones and no painkillers at all. You think you're at risk? You have the luxury to worry about heat and naloxone. We worry about if we can afford paracetamol. Your warnings are rich people problems. The real danger is not having any option at all. Stop preaching to the choir and fix the system that leaves millions without medicine before you lecture about how to use the one you have.