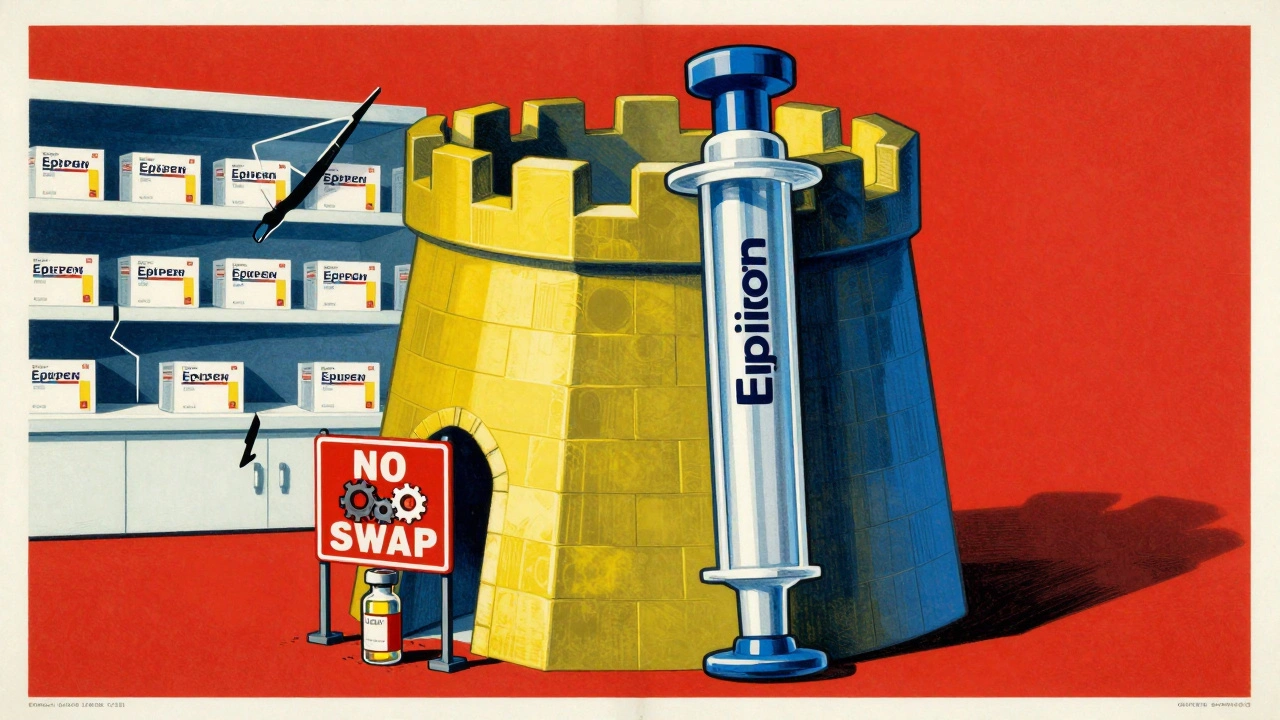

Imagine you need an EpiPen. Your doctor prescribes it. Your pharmacy gives you a generic epinephrine injection - but the auto-injector device is still the branded one. You’re told you can’t swap it out. Why? Because in the world of combination products, generic combination products aren’t just two pills in one box. They’re a drug and a device working as one system - and the law doesn’t let you mix and match.

What Exactly Is a Combination Product?

A combination product isn’t a new drug or a new device. It’s both, fused together in a way that neither works right without the other. Think of an inhaler that delivers asthma medicine, an insulin pen with a built-in dose counter, or an auto-injector like an EpiPen. The drug doesn’t just float in the air - it’s delivered by a mechanism designed to work with it. That’s why the FDA calls these products combination products. They’re regulated as a single unit, not two separate parts.

The FDA has three official ways to define them:

- Components are physically or chemically combined - like a prefilled syringe with medicine already inside.

- Components are packaged together - like a blister pack with a pill and a special applicator.

- Components are sold separately but labeled to be used together - like a generic epinephrine vial and a specific auto-injector designed only for that vial.

Here’s the catch: if you replace just one part - say, the drug - with a generic version, but keep the branded device, you’re not getting the same product. The FDA requires the entire system to be tested as one. That’s why a generic drug in a branded device doesn’t count as a generic combination product.

Why Can’t You Just Swap the Drug?

Traditional generic substitution works like this: you get a cheaper version of the same pill, same dose, same effect. It’s simple. But with combination products, it’s not that easy.

Take the EpiPen. The device isn’t just a plastic casing. It’s engineered to deliver the exact right amount of epinephrine at the exact right speed. The needle length, spring tension, trigger force, even the grip texture - all of it matters. If you use a generic epinephrine solution in a branded EpiPen, the delivery might be too slow, too fast, or not deep enough. The FDA says that’s not safe. So even if the drug is identical, the system isn’t.

That’s why the FDA requires a full comparative analysis for any generic version. Manufacturers must prove that their generic device performs exactly like the original - not just in the lab, but in real hands. That means human factors testing: real people - including those with arthritis, shaky hands, or low vision - trying to use the device under stress. If 10% of users can’t activate it correctly, the product gets rejected.

The Hidden Cost of Complexity

Developing a generic combination product isn’t like making a generic tablet. It’s more like reverse-engineering a Swiss watch.

On average, it takes 18 to 24 months longer to develop a generic drug-device combo than a regular generic. The cost? Between $2.1 million and $3.7 million extra. That’s why only 17 companies in the U.S. have successfully brought a complex generic combination product to market - compared to over 120 companies making simple generics.

And even when they do, approval is slow. In 2023, 92% of standard generic drug applications were approved within 10 months. For complex combination products? Only 47% made it that fast. The biggest reason for rejection? Inadequate device comparison data. Nearly half of all rejected applications were turned down because the manufacturer didn’t prove their device worked just like the original.

That’s why prices stay high. While over 90% of single-drug prescriptions are filled with generics, only 12% of combination products are. Branded products still hold 68% of the market. Patients pay 37% more out-of-pocket for these products than they do for regular generics.

Real-World Confusion in Pharmacies

Pharmacists are caught in the middle.

A 2024 survey by the National Community Pharmacists Association found that 68% of pharmacists have run into substitution confusion with combination products. Over 40% get at least one patient complaint per month. One common scenario: a patient gets a generic drug refill, but the device is different. They ask, “Why isn’t this the same?” The pharmacist doesn’t know how to explain it.

On Reddit, a thread titled “Why can’t my generic EpiPen substitute normally?” had 287 comments. One pharmacist wrote: “The auto-injector device is considered part of the product, so even if you have a generic epinephrine, you need the specific generic auto-injector approved for substitution - which often doesn’t exist yet.”

Doctors are affected too. A 2024 AMA survey showed that 57% of physicians have had to delay treatment because a patient couldn’t get the right combination product. On average, each delay lasted over three business days. That’s not just inconvenient - it’s dangerous for someone with severe allergies or asthma.

What’s Changing? New Rules, New Hope

There’s movement. The FDA released updated guidance in April 2024 on how to prove device equivalence. They’re also hiring more reviewers - 32 new specialists since 2022 - and launching the “Complex Generic Initiative 2.0,” aiming to cut approval times by 30% by 2026.

States are stepping in too. California and Massachusetts have introduced bills to let pharmacists substitute combination products under strict rules - if both the drug and device are generic and approved as a matched pair. That’s a big shift. Right now, most state substitution laws only cover single-drug products. These new laws would finally recognize that two generics - one for the drug, one for the device - can equal one branded product.

Industry analysts believe generic penetration in this space could jump from 12% to 35% by 2027. That would mean millions of patients saving hundreds of dollars a year.

What Patients and Providers Need to Know

If you’re prescribed a combination product:

- Ask if a generic version exists - not just for the drug, but for the entire system.

- Don’t assume a generic drug in a branded device is safe or legal to use together.

- Check the label: if it says “for use with [specific device],” that’s a sign it’s part of a regulated system.

- If your pharmacy can’t fill it, ask them to contact the manufacturer or your prescriber. Sometimes, a different generic combination product exists that’s approved.

For prescribers: write prescriptions clearly. Don’t just say “epinephrine auto-injector.” Specify the brand or the generic combination product by name. That avoids confusion at the pharmacy.

The goal isn’t to stop innovation. It’s to make sure that when a cheaper, safer alternative exists, patients can actually get it. Right now, the system is broken. But change is coming - slowly, but surely.

Why This Matters

This isn’t just about money. It’s about access. People with chronic conditions - asthma, diabetes, severe allergies - rely on these devices daily. When they can’t afford them, they skip doses. They delay refills. They risk emergencies.

Generic combination products could save the U.S. healthcare system billions. But only if we fix the rules. Only if we stop treating a drug and a device as separate when they’re designed to be one.

The future of generic substitution isn’t just pills in bottles. It’s drugs in devices - and the law has to catch up.

Can I use a generic drug with a branded device if they’re for the same condition?

No. The FDA treats combination products as a single unit. Even if the drug is identical, the device is part of the therapeutic system. Using a generic drug with a branded device (or vice versa) isn’t approved and could be unsafe. Always use the full generic combination product if one exists - not mixed components.

Why are there so few generic combination products on the market?

Developing them is expensive and complex. Manufacturers must prove the generic device works exactly like the original - not just in theory, but with real users. Human factors testing, device comparisons, and regulatory reviews take 18-24 months longer than standard generics. Only 17 companies have the resources to do this, which limits competition and keeps prices high.

Are there any generic combination products approved right now?

Yes, but they’re rare. Examples include generic versions of the EpiPen (with a matching auto-injector), some generic inhalers like ProAir HFA, and a few insulin pens. However, for every branded combination product, there’s usually only one or two generic options - and often none at all. The FDA has approved fewer than 50 generic combination products since 2010.

What’s the difference between a combination product and a co-packaged product?

A combination product is designed to work as one system - the drug and device are interdependent. A co-packaged product is just two separate items sold together, like a pill and a measuring cup. The FDA only regulates the latter as a combination product if they’re labeled specifically for use together. Otherwise, they’re treated as two separate products.

Can my pharmacist substitute a generic combination product without asking me?

In most states, no. Current substitution laws only allow pharmacists to swap single-drug generics. For combination products, substitution is only allowed if the state has passed new legislation (like California’s AB-1847) and both the drug and device are FDA-approved as a matched generic pair. Always check with your pharmacist - don’t assume substitution is automatic.

Richard Eite

December 8, 2025 AT 16:14Philippa Barraclough

December 10, 2025 AT 09:53Jennifer Blandford

December 10, 2025 AT 15:39Brianna Black

December 11, 2025 AT 01:23om guru

December 11, 2025 AT 06:24Shubham Mathur

December 12, 2025 AT 00:53Ronald Ezamaru

December 12, 2025 AT 04:48Lola Bchoudi

December 13, 2025 AT 17:15Morgan Tait

December 15, 2025 AT 04:19Ryan Brady

December 15, 2025 AT 14:39Gilbert Lacasandile

December 16, 2025 AT 00:09Tim Tinh

December 17, 2025 AT 23:03Taya Rtichsheva

December 18, 2025 AT 21:34Stacy Tolbert

December 20, 2025 AT 00:16Darcie Streeter-Oxland

December 21, 2025 AT 16:38