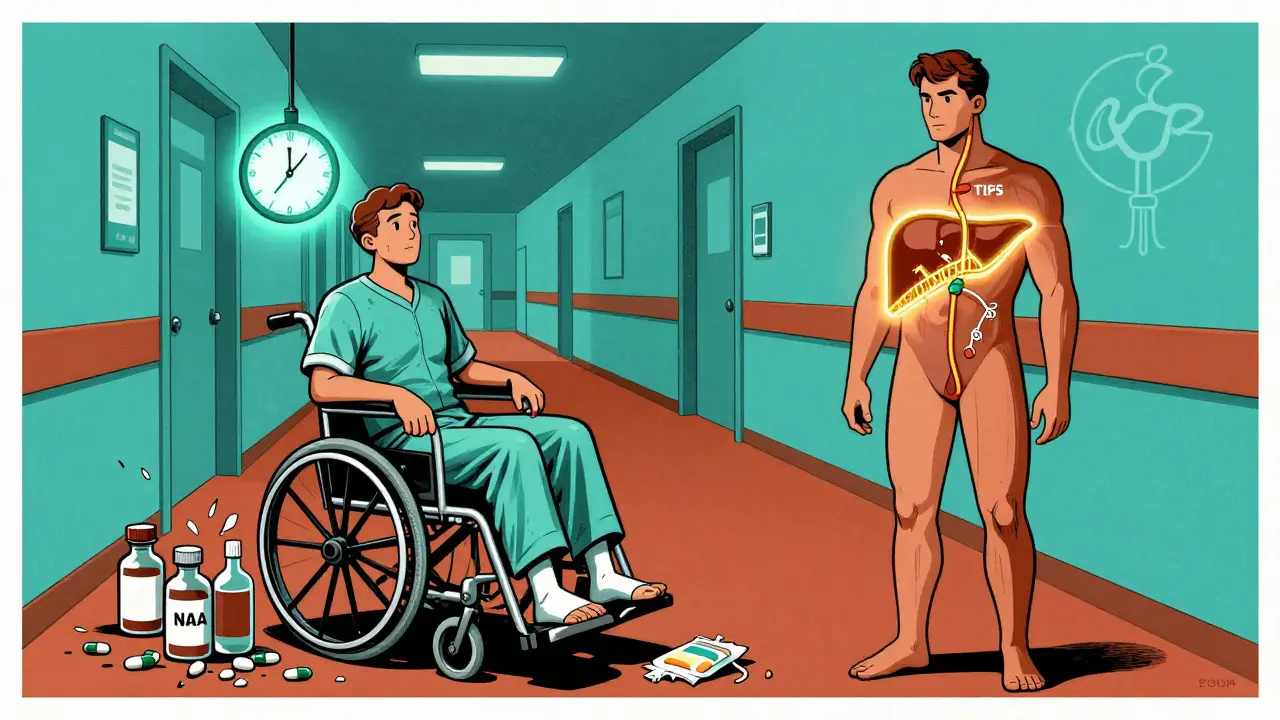

When your liver is failing, your kidneys don’t just slow down-they can shut down completely, even if they’re not damaged. This isn’t a coincidence. It’s hepatorenal syndrome, a deadly chain reaction triggered by advanced liver disease. It’s not a kidney problem. It’s a liver problem that kills the kidneys through blood flow chaos. And it happens faster than most people realize.

What Exactly Is Hepatorenal Syndrome?

Hepatorenal syndrome (HRS) is kidney failure that happens in people with severe liver disease-usually cirrhosis. The kidneys aren’t broken. They’re not scarred. They’re not blocked. They’re just starving for blood. And that’s because the liver has collapsed, throwing the whole body’s circulation into chaos.

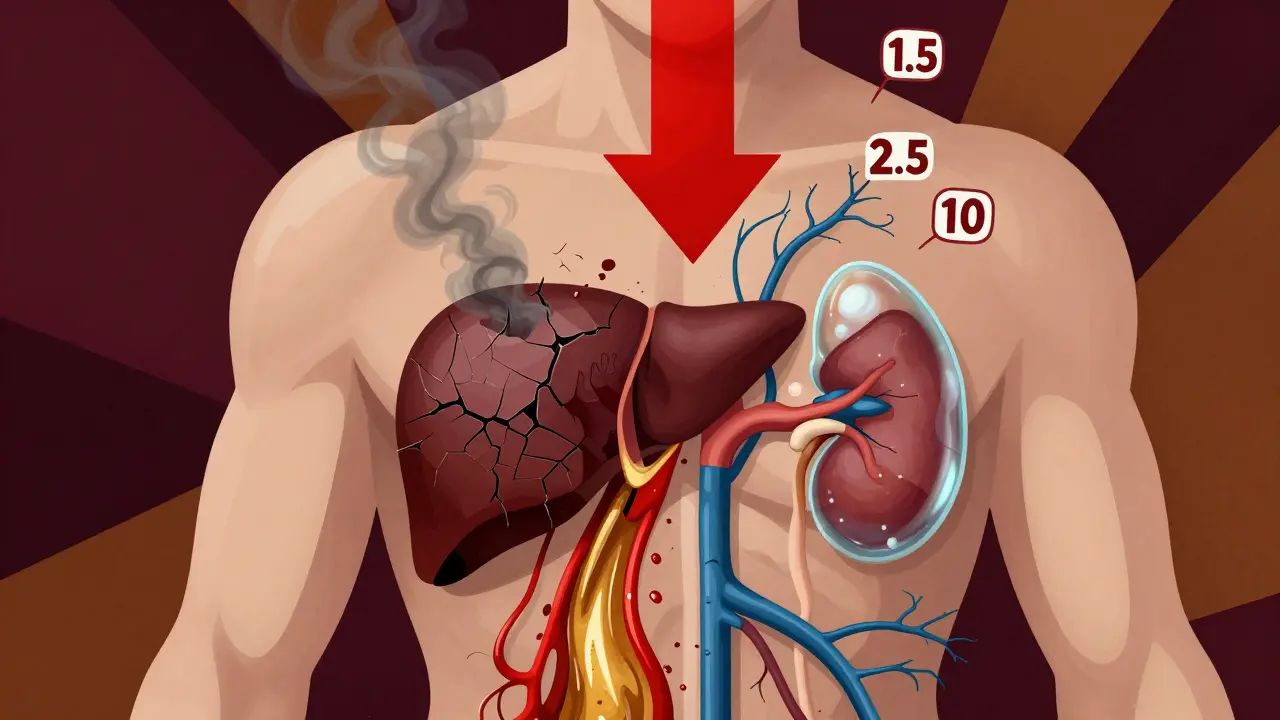

Think of it like this: your liver is supposed to regulate blood pressure and flow. When it’s cirrhotic, blood backs up in the abdomen (ascites), and vessels in the gut dilate like overinflated balloons. This pulls fluid away from the heart and major arteries. Your body thinks you’re bleeding out. So it tightens every blood vessel it can-especially the ones going to your kidneys. No blood flow. No filtration. Creatinine spikes. Kidneys fail.

This isn’t normal kidney disease. It’s a functional collapse. Biopsies show clean, healthy kidney tissue. But the numbers scream failure: serum creatinine over 1.5 mg/dL, urine sodium under 10 mmol/L, no protein in the urine. If you have cirrhosis and these signs, and you’ve ruled out infection, dehydration, or NSAIDs, you’re looking at HRS.

The Two Types: Fast and Slow Death

HRS doesn’t come in one flavor. It comes in two, and they’re worlds apart in speed and survival.

Type 1 is a medical emergency. Creatinine doubles to over 2.5 mg/dL in under two weeks. Survival without treatment? Median of 2 weeks. It often shows up after a spontaneous infection in the belly (spontaneous bacterial peritonitis), a GI bleed, or heavy alcohol binges. Patients crash fast. One day they’re managing ascites. The next, they’re on dialysis.

Type 2 creeps in. Creatinine stays between 1.5 and 2.5 mg/dL. It’s tied to stubborn ascites that won’t go away, even with high-dose diuretics. It’s not as immediately deadly as Type 1, but it’s just as hopeless without a transplant. People live months, sometimes a year or two, but their kidneys keep slipping. And every drop in function makes transplant harder.

Both types are fatal without intervention. And neither responds to fluids or diuretics like regular kidney failure. That’s the red flag.

What Triggers It? The Hidden Causes

Most HRS cases don’t come out of nowhere. Something pushes the liver over the edge.

- Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (SBP) - triggers 35% of cases. Even a low-grade belly infection can set off the cascade.

- Upper GI bleeding - 22%. Blood in the gut pulls fluid out of circulation, worsening the blood pressure drop.

- Acute alcoholic hepatitis - 11%. A sudden alcohol binge can wreck an already fragile liver.

- Nephrotoxic drugs - NSAIDs, antibiotics like gentamicin, contrast dye for scans. These are avoidable killers.

- Large-volume paracentesis without albumin - removing too much belly fluid too fast without replacing it with protein can crash blood pressure.

One study found that 68% of HRS patients had a clear trigger. That means nearly 7 out of 10 cases could’ve been prevented with better monitoring and care.

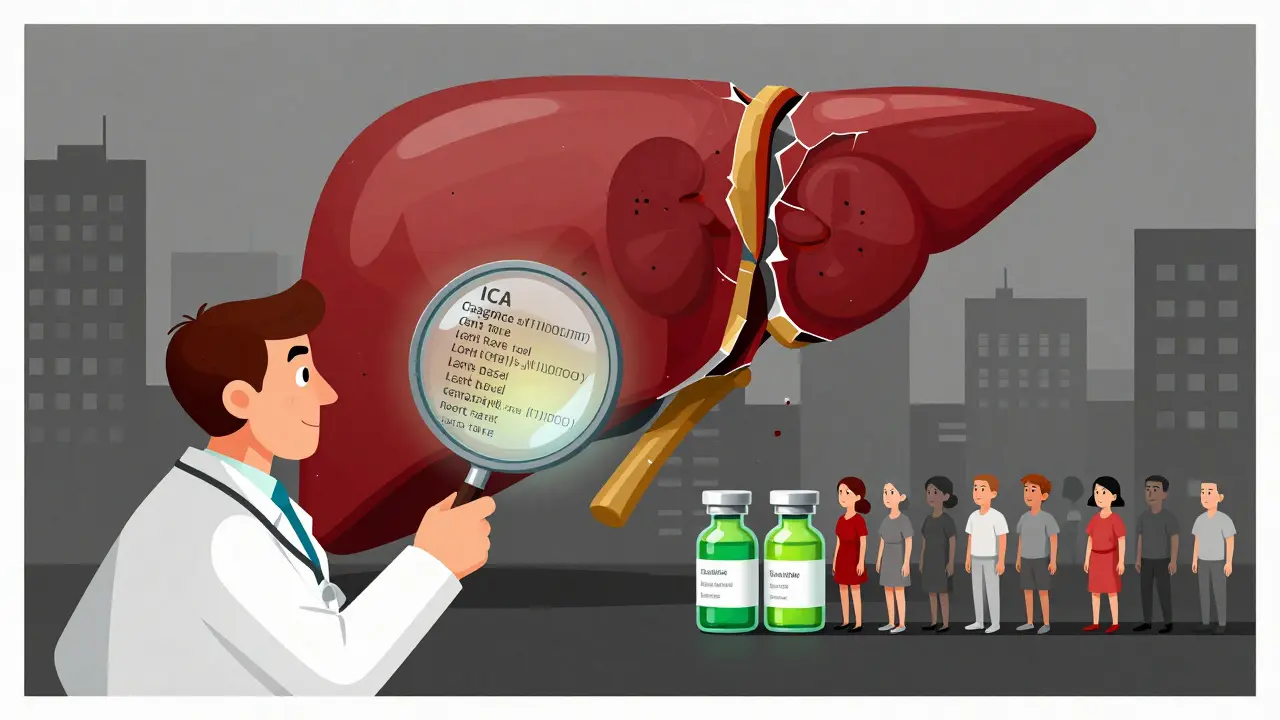

How Is It Diagnosed? The Rules

You can’t just look at creatinine. You have to rule everything else out. That’s why HRS is misdiagnosed in 25-30% of cases.

The 2022 International Club of Ascites (ICA) criteria are the gold standard:

- You have cirrhosis and ascites.

- Your creatinine is above 1.5 mg/dL.

- You’ve stopped diuretics for at least 2 days.

- You’ve gotten 1 gram per kg of albumin (up to 100g) over 48 hours and saw no improvement.

- No signs of structural kidney damage: no proteinuria (>500 mg/day), no hematuria, no kidney stones or tumors.

- Your urine sodium is below 10 mmol/L, and your urine osmolality is higher than your blood’s.

If you meet all these, you have HRS. If you miss one, you might have something else-like acute tubular necrosis from sepsis or dehydration. And those need totally different treatment.

Treatment: What Actually Works

There’s no magic pill. But there are two proven paths: drugs and transplant.

For Type 1 HRS: The only treatment with strong evidence is terlipressin (a vasoconstrictor) plus albumin. Terlipressin tightens blood vessels, redirects blood to the kidneys, and can reverse kidney failure in about 44% of cases. It’s given IV every 4-6 hours. Side effects? Severe abdominal cramps, low blood pressure, heart rhythm problems, and ischemia in fingers or toes. One patient on a liver forum said their creatinine dropped from 3.8 to 1.9 in 10 days-but they had to reduce the dose because the pain was unbearable.

Terlipressin isn’t FDA-approved in the U.S. unless it’s the branded version, Terlivaz, which costs about $1,100 per vial. A 14-day course? Around $13,200. Many hospitals still use off-label alternatives like midodrine and octreotide, but they’re less effective.

For Type 2 HRS: Terlipressin helps, but so does TIPS-a procedure that creates a shunt inside the liver to reduce portal pressure. It works in 60-70% of cases. But it has a 30% risk of triggering hepatic encephalopathy, a dangerous brain fog from liver toxins. So it’s not for everyone.

Albumin is always part of the treatment. It’s not just a filler. It pulls fluid back into the bloodstream, stabilizes blood pressure, and improves kidney response to drugs. Patients get 1g/kg on day one, then 20-40g daily after.

Transplant: The Only Real Cure

If you have HRS, your only real shot at long-term survival is a liver transplant.

Without it, 1-year survival for Type 1 HRS is under 20%. With vasoconstrictors alone? About 39%. But with a transplant? Over 71% survive a year. That’s not a small difference-it’s life or death.

Because HRS is so deadly, transplant centers now list patients earlier. The MELD-Na score-which predicts death risk-now includes sodium levels and kidney function. If your score hits 25 or higher, you’re prioritized. One Reddit user shared their husband’s MELD-Na was 28 after six weeks of failed meds. They were placed on the transplant list immediately.

And here’s the hard truth: even if terlipressin works, most patients still need a transplant. The liver is still cirrhotic. The system is still broken. The kidneys might recover, but the root cause remains.

Why So Many Get It Wrong

Doctors outside transplant centers often don’t know how to spot HRS. A 2021 study showed only 58% of non-specialists correctly diagnosed it from case scenarios.

Why? Because they treat it like regular kidney failure. They give fluids. They push diuretics. They delay albumin. They don’t check urine sodium. They don’t know the ICA criteria.

At Mayo Clinic, they created a standard protocol: alert the hepatology team immediately, stop nephrotoxins, give albumin within hours, start terlipressin if criteria are met. Result? Diagnosis time dropped from 5.3 days to 1.8 days. Vasoconstrictor use jumped from 54% to 89%. And 30-day survival rose by 22%.

Most hospitals still don’t have this. Community clinics? Often no hepatology consult. No protocol. No awareness. That’s why 78% of patients experience diagnostic delays. And 63% get misdiagnosed.

What’s Coming Next?

Research is moving fast. The FDA approved terlipressin for pediatric HRS in January 2023. That’s new. And new drugs are in trials:

- Alfapump-a device that drains ascites automatically, helping Type 2 HRS patients.

- PB1046-a new vasopressin agonist that may work better than terlipressin with fewer side effects.

- NGAL biomarker-a urine test that could predict HRS before creatinine even rises. Early data shows it’s accurate at 0.8 ng/mL.

But access remains a crisis. In sub-Saharan Africa, 89% of HRS patients get only supportive care. In North America, 63% get vasoconstrictors. That’s not a medical gap-it’s an equity gap.

By 2027, experts believe new therapies could cut HRS deaths by 30-40%. But only if we fix how we diagnose it, treat it, and who gets access to it.

What Patients Should Know

If you or someone you love has cirrhosis and your kidneys are failing:

- Don’t assume it’s just dehydration or a bad reaction to a drug.

- Ask for a hepatologist consult-immediately.

- Request the ICA diagnostic criteria be applied.

- Insist on albumin and terlipressin if you meet Type 1 criteria.

- Get on the transplant list now, even if your creatinine isn’t sky-high.

- Track your sodium levels. Low sodium means worse prognosis.

Hepatorenal syndrome doesn’t wait. It doesn’t care if you’re insured. It doesn’t care if your doctor missed it. It only cares if you act fast.

Is hepatorenal syndrome the same as kidney disease?

No. Hepatorenal syndrome isn’t kidney disease. The kidneys are structurally normal. The failure is caused by blood flow problems from advanced liver disease. It’s a functional problem, not a structural one.

Can you survive hepatorenal syndrome without a transplant?

Survival without transplant is very low. Type 1 HRS has a median survival of just 2 weeks without treatment. With terlipressin and albumin, 1-year survival rises to about 39%. But long-term survival only becomes likely with a liver transplant-where 1-year survival jumps to over 71%.

What’s the difference between Type 1 and Type 2 HRS?

Type 1 HRS is rapid and life-threatening: creatinine doubles to over 2.5 mg/dL in under two weeks. Type 2 is slower, with creatinine between 1.5 and 2.5 mg/dL, usually tied to stubborn ascites. Type 1 needs urgent drug treatment. Type 2 may respond to TIPS or long-term vasoconstrictors.

Why is albumin used in treatment?

Albumin helps restore blood volume and pressure. In liver disease, low albumin pulls fluid into the belly. Giving IV albumin pulls fluid back into circulation, improves kidney blood flow, and makes vasoconstrictors like terlipressin work better.

Can medications like NSAIDs cause hepatorenal syndrome?

NSAIDs don’t cause HRS directly, but they can trigger it in people with advanced liver disease. They reduce blood flow to the kidneys and interfere with natural blood pressure regulation. In cirrhosis, even small doses can push someone into HRS.

How can I tell if my doctor suspects HRS?

If your doctor checks your urine sodium, stops your diuretics, gives you albumin, and orders terlipressin or TIPS, they’re likely considering HRS. If they’re just giving fluids or blaming dehydration, they may not be aware of the diagnostic criteria. Ask specifically if they’ve ruled out HRS using the ICA guidelines.

Is terlipressin available everywhere?

No. Terlipressin is FDA-approved in the U.S. only as Terlivaz, which is expensive and hard to get outside major transplant centers. Many hospitals use off-label combinations like midodrine and octreotide, which are less effective. In low-income countries, it’s often unavailable entirely.

What’s the role of MELD-Na in HRS?

MELD-Na is the score used to prioritize liver transplant candidates. Since 2022, it includes sodium levels and kidney function, so HRS patients get higher scores and move up the list faster. A MELD-Na above 25 usually means urgent listing.

Next Steps: What to Do Right Now

If you have cirrhosis and your creatinine is rising:

- Stop all NSAIDs, diuretics, and unnecessary meds immediately.

- Ask for a serum sodium test and urine sodium test.

- Request albumin infusion-1g/kg on day one.

- Push for a hepatology consult within 24 hours.

- Ask: “Could this be hepatorenal syndrome? Are we following the ICA criteria?”

- If you’re eligible, get on the transplant list. Don’t wait for kidney failure to get worse.

Hepatorenal syndrome doesn’t care about your insurance, your doctor’s schedule, or how busy the hospital is. It moves fast. And the only thing that stops it is knowledge, speed, and action.

Emily P

December 19, 2025 AT 15:47This is the kind of post that makes me want to hug a hepatologist.

Just... wow. I didn’t realize kidney failure in cirrhosis wasn’t even a kidney problem. Mind blown.

Dikshita Mehta

December 21, 2025 AT 08:14As a nephrology nurse in Mumbai, I see this all the time but rarely diagnosed early. Many patients are given diuretics until their kidneys give out. The ICA criteria are lifesaving-but only if someone knows them. Thank you for sharing this in such clear detail.

Albumin isn’t just a filler-it’s the bridge between collapse and recovery.

Jedidiah Massey

December 22, 2025 AT 12:36Let’s be clear: HRS isn’t ‘kidney failure’-it’s a hemodynamic catastrophe secondary to splanchnic vasodilation and systemic hypotension, mediated by nitric oxide overproduction and renal vasoconstriction. The ICA criteria are elegantly designed to exclude ATN, but clinicians still confuse functional with structural AKI. Terlipressin’s mechanism-V1 receptor agonism-is superior to midodrine’s alpha-1 agonism, which lacks renal selectivity. Also, the MELD-Na score’s inclusion of sodium is biologically sound: hyponatremia reflects worsening circulatory dysfunction. Case closed.

Sarah McQuillan

December 22, 2025 AT 17:32So… you’re telling me this whole thing is just because the liver’s ‘broken’? Like, we’re supposed to believe that a *liver* can cause kidneys to shut down? That’s just… poetic. I mean, I’ve seen people with cirrhosis live for years with dialysis-so maybe it’s not so bad? Maybe the doctors are just overcomplicating it? I mean, I read on a forum once that kidneys just ‘get tired’-like a phone battery. Maybe we just need to let them rest?

pascal pantel

December 23, 2025 AT 06:14Terlipressin costs $13k? And you’re telling me this isn’t a pharma scam? Let me guess-this drug was developed by a company that also makes liver transplants. Classic. Also, ‘MELD-Na’? That’s not a score, that’s a marketing gimmick to push transplant tourism. And don’t even get me started on ‘albumin’-it’s just salt water with a fancy label. Real medicine doesn’t need $1,100 vials. Just give them salt and water. Done.

holly Sinclair

December 24, 2025 AT 04:45It’s fascinating how the body doesn’t distinguish between organs the way medicine does. The liver isn’t just ‘broken’-it’s screaming. And the kidneys? They’re not failing. They’re listening. They’re responding to the chaos like a soldier on the front lines who’s been told to hold the line… but no one’s coming to reinforce them. No blood. No pressure. No hope. So they shut down-not because they’re damaged, but because they’re trying to survive the collapse of the whole system. It’s not a disease. It’s a tragedy of physiology. And the worst part? We have the tools to stop it. We just don’t use them fast enough. Or evenly. Or compassionately. The real crisis isn’t the syndrome-it’s the delay. The bureaucracy. The cost. The fact that someone in rural Nebraska might wait weeks for a consult while someone in Boston gets terlipressin by noon. Medicine has become a geography problem. And the kidneys? They don’t care where you live. They just stop working.

And yet-we still treat this like a technical glitch. Like a code error. We run labs, we tweak doses, we count creatinine like it’s a scoreboard. But it’s not. It’s a cry. A silent, systemic cry. And we’re still typing out protocols instead of holding hands.

I wonder if the first person who noticed this pattern-back in the 1950s-cried when they realized: ‘It’s not the kidneys. It’s the liver. And the liver is dying alone.’

Maybe that’s why I can’t sleep after reading this. Not because it’s complex. But because it’s so… human.

James Stearns

December 24, 2025 AT 16:22It is, without question, an extraordinary and profoundly disconcerting revelation that the kidneys, despite their structural integrity, are rendered functionally inert by the systemic derangement wrought by hepatic decompensation. One must, therefore, contemplate the ontological implications: Is the kidney truly ‘failing,’ or is it merely… obeying? This raises not only clinical but philosophical questions regarding agency within the human organism. Is the kidney a passive victim? Or is it, in its own way, exercising a form of biological autonomy? The answer, I suspect, lies beyond the ICA criteria-and into the realm of metaphysical physiology.

Vicki Belcher

December 24, 2025 AT 20:44OMG I just cried reading this 😭

My uncle had this and they didn’t diagnose it until it was too late…

PLEASE tell your doctor about albumin and terlipressin!!

Don’t wait!!

❤️

anthony funes gomez

December 24, 2025 AT 23:23Terlipressin… V1 agonist… splanchnic vasodilation… MELD-Na… albumin… TIPS… HRS-1… HRS-2… ICA… SBP… NSAID… cirrhosis… ascites… creatinine… sodium… osmolality… proteinuria… hematuria… hepatorenal… functional… structural… nephrotoxic… vasoconstrictor… vasopressin… paradoxical… hypovolemia… hyperdynamic circulation… systemic inflammation… nitric oxide… endothelin… renin-angiotensin-aldosterone… sympathetic nervous system… renal perfusion pressure… glomerular filtration rate… tubuloglomerular feedback…

…I’m tired.

Sahil jassy

December 26, 2025 AT 16:17From India: we don’t have terlipressin here. No TIPS. No hepatology teams. Just diuretics and hope. But we know the signs. We watch the urine sodium. We give albumin if we can. We tell families: ‘This isn’t kidney failure. It’s liver failure. And you need a transplant.’ We don’t have the tools. But we have the eyes. And we’re not giving up.

Thank you for writing this. Someone needed to say it.

William Storrs

December 27, 2025 AT 13:19Hey. If you’re reading this and someone you love has cirrhosis and their creatinine is rising-don’t wait. Don’t hope. Don’t say ‘maybe it’s just dehydration.’

Ask for albumin. Ask for terlipressin. Ask for the ICA criteria. Ask for a transplant consult.

They’re not being dramatic. They’re not overreacting.

They’re fighting for their life.

And you? You’re their voice.

Be loud.

Be urgent.

Be relentless.

They’re counting on you.

Chris Clark

December 28, 2025 AT 06:17So like… if your liver is trash, your kidneys just give up? That’s wild. I thought kidneys were tough. Like, they filter everything. But turns out they’re just… following the liver’s lead? Kinda like a puppy that stops eating when its owner’s sad.

Also-terlipressin? Sounds like a villain in a Marvel movie. ‘Behold, I am Terlipressin! I shall constrict thy vessels!’

But seriously-this is why I love science. It’s like the body’s got a whole drama series going on and we’re just catching up on season 3.

Gloria Parraz

December 28, 2025 AT 16:24I’ve watched my sister go through this. They told her it was ‘just kidney trouble.’ She was on dialysis for three weeks before someone finally said, ‘Wait-this is HRS.’

She got terlipressin. She got albumin. Her creatinine dropped.

And then? She got on the transplant list.

Now she’s alive.

Don’t let them tell you it’s ‘just a number.’

It’s not a number. It’s your sister. Your dad. Your friend.

Ask the questions.

Push for the tests.

Don’t let them ignore it.

You are not being ‘difficult.’

You are being their lifeline.