When your doctor writes a prescription, you might assume the pharmacy will give you the brand-name drug you asked for. But more often than not, you’ll walk out with a generic version-cheaper, just as effective, and approved by the FDA. Yet, not all doctors are comfortable with that switch. In fact, some medical societies have taken official stances against it. Why? And what does that mean for you?

Generic drugs aren’t just cheap copies

The FDA requires generic drugs to have the same active ingredient, strength, dosage form, and route of administration as the brand-name version. They must also prove they’re bioequivalent-meaning they deliver the same amount of drug into your bloodstream at the same rate. The acceptable range? 80% to 125% of the brand’s concentration. That’s not a loophole. It’s science.

For most drugs, this works perfectly. Over 90% of prescriptions filled in the U.S. are generics, and they account for just 23% of total drug spending. That’s billions saved every year. But for some medications, even tiny differences matter.

When small changes can cause big problems

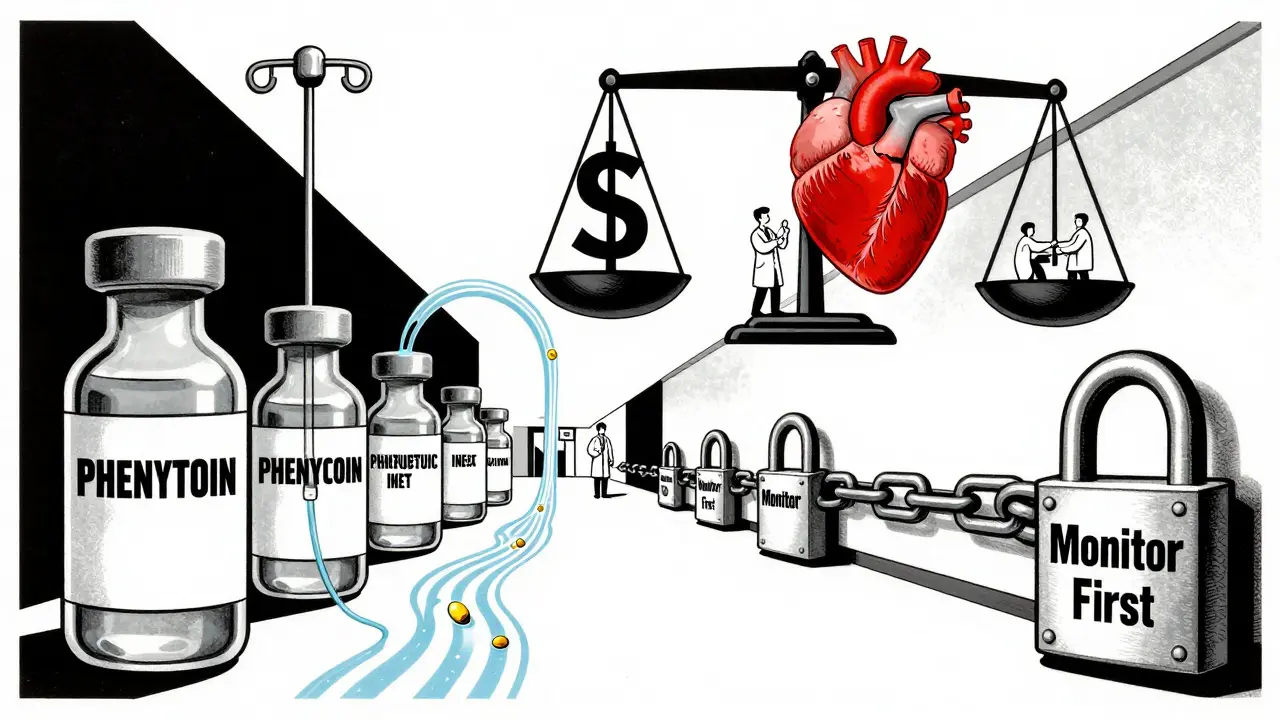

Drugs with a narrow therapeutic index (NTI) are the exception. These are medications where the difference between a helpful dose and a dangerous one is razor-thin. Think blood thinners like warfarin, thyroid meds like levothyroxine, or seizure drugs like phenytoin.

The American Academy of Neurology (AAN) has been clear: don’t substitute generic versions of anticonvulsants without the prescriber’s approval. Why? Because even small shifts in drug levels can trigger breakthrough seizures. A 2022 survey of neurologists found that 68% believed generic substitutions had led to complications in their patients. That’s not speculation-it’s clinical experience.

It’s not just neurology. Cardiologists, endocrinologists, and psychiatrists often express similar concerns. The FDA says generics are safe. But medical societies aren’t just looking at lab data-they’re watching real people. And when someone has a seizure, a stroke, or a thyroid crisis after a switch, the blame doesn’t go to the patient. It goes to the system.

Doctors aren’t against generics-they’re against uncertainty

The American College of Physicians supports generic substitution for most drugs. So does the American Medical Association. But both organizations also emphasize consistency. If a patient is stable on a brand-name drug, switching them to a generic-even one approved by the FDA-can introduce risk.

One pharmacist in Edinburgh told me about a 72-year-old woman with atrial fibrillation. She’d been on warfarin for 12 years. Her INR levels were rock steady. Then, her insurance forced a switch to a generic. Her INR spiked. She ended up in the hospital with a minor bleed. The doctor didn’t blame the generic. He blamed the lack of communication. No one told him. No one checked her levels after the switch.

That’s the real issue: substitution without monitoring. The guidelines don’t say “never use generics.” They say: “know when it’s safe, and when it’s not.”

How drug names make or break safety

Here’s something most patients don’t know: generic drugs don’t just have different labels. They have different names.

The American Medical Association’s United States Adopted Names (USAN) Council decides what nonproprietary names drugs get. Their job? Make names clear, distinct, and safe. No two drugs should sound or look alike. One wrong letter, and a nurse could give the wrong drug.

For example, the name “lamotrigine” is carefully chosen to avoid confusion with “lamivudine,” a completely different antiviral drug. The council avoids stems that are too similar to existing ones. They even have a pronunciation guide. Why? Because 1 in 5 medication errors involve look-alike or sound-alike names. And when a pharmacist substitutes a generic, they’re relying on that name to be clear.

It’s not about branding. It’s about preventing mistakes before they happen.

Oncology: where generics get a free pass

Then there’s cancer. In oncology, generic drugs are used off-label all the time. The National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) Guidelines-used by hospitals and insurers to determine coverage-list dozens of off-label uses for generic chemotherapy agents. If a generic drug works for one cancer, it’s often considered safe for another, even if it’s not officially approved for that use.

Why the difference? Because in cancer care, time matters more than perfection. If a generic version of a drug is available and the patient can’t afford the brand, waiting isn’t an option. The NCCN treats these drugs as interchangeable within their class. And because cancer drugs are often given in controlled settings-hospitals, infusion centers-the risk of error is lower.

That’s the key: context. Where you get the drug, who administers it, and how closely it’s monitored all affect whether substitution is safe.

State laws vs. medical advice

Here’s where things get messy. In some states, pharmacists can substitute generics automatically-unless the doctor writes “dispense as written.” In others, substitution is banned for NTI drugs entirely. In a few, it’s allowed only if the patient consents.

But medical society guidelines don’t always match state law. A neurologist in Texas might tell a pharmacist not to substitute phenytoin. But if the state allows it, and the patient’s insurance pushes for the cheaper version, the pharmacist has to choose: follow the law or follow the doctor.

That’s why many prescribers now write “DAW 1” on prescriptions-meaning “dispense as written.” It’s their way of saying: I know the risks. I’ve made the call. Don’t swap it.

What patients need to know

If you’re on a drug with a narrow therapeutic index-epilepsy, thyroid, heart rhythm, blood thinning-ask this:

- Is this a drug where small changes matter?

- Have I been stable on my current version?

- Has my doctor approved a switch?

- Will my levels be checked after the switch?

If you’re on a drug like amoxicillin, metformin, or lisinopril, generics are almost always fine. No need to worry. But if you’re on phenytoin, levothyroxine, or cyclosporine-don’t assume. Ask.

And if your pharmacist switches your drug without telling you? Speak up. You have the right to know what you’re taking-and the right to refuse a substitution if you’re not comfortable.

The future: alignment, not opposition

Medical societies aren’t fighting the FDA. They’re asking for nuance. The FDA’s Orange Book rates drugs by therapeutic equivalence. But those ratings don’t capture everything. Real-world outcomes do.

More guidelines are starting to reflect that. The AAN isn’t saying generics are bad. They’re saying: for anticonvulsants, don’t switch without a plan. The AMA isn’t against cost savings-they’re against silent switches that put patients at risk.

The goal isn’t to block generics. It’s to make sure they’re used safely. That means doctors, pharmacists, and patients all need to be on the same page. Because when it comes to your health, the cheapest option isn’t always the safest one.

Matthew Miller

January 11, 2026 AT 17:23Let’s be real-this whole ‘generic drugs are dangerous’ narrative is just pharma’s way of keeping prices high. The FDA’s bioequivalence standards are rock solid. If you’re having issues, it’s not the drug-it’s the lack of follow-up monitoring. Stop blaming generics and start blaming lazy prescribing.

Madhav Malhotra

January 11, 2026 AT 19:19As someone from India where generics save lives daily, I’m surprised by the drama here. In my village, people rely on generics for diabetes, BP, even epilepsy meds. Yes, some need monitoring-but the system works when doctors and pharmacists talk. Maybe the US needs more communication, not fewer generics.

Jason Shriner

January 13, 2026 AT 13:05So… the FDA says it’s fine, but doctors are like ‘nahhh’? 😒

Meanwhile, my insurance company is out here playing chess with my thyroid med like it’s Monopoly.

Someone get these neurologists a hobby. Maybe knitting? Or reading actual science?

Also-why is everyone acting like levothyroxine is a magic potion? It’s a hormone. Not a god.

Alfred Schmidt

January 14, 2026 AT 03:04I’ve seen it. I’ve seen it. My cousin went from brand Synthroid to generic-INR went wild, she had panic attacks, her hair fell out, she ended up in the ER. And the pharmacist? Didn’t even call the doctor. Just swapped it. And now? They’re saying ‘it’s not the drug, it’s the system’? NO. It’s the SYSTEM that didn’t protect her. This isn’t ‘nuance’-this is negligence. Someone needs to be held accountable. Not just ‘ask your doctor’-that’s a cop-out.

Roshan Joy

January 14, 2026 AT 07:45Good post! 🙌 I’ve been on levothyroxine for 8 years and switched generics twice-no issues. But I always check with my endo first and get blood work after. It’s not about fear-it’s about being proactive. Also, love the part about drug names! So many errors happen because ‘metoprolol’ and ‘metformin’ look too similar. Little things matter. 👏

Michael Patterson

January 14, 2026 AT 21:43Look, I get it, generics are cheaper, but let’s not pretend this is all about cost savings. The real issue is that insurance companies are making decisions that should be made by clinicians. And yeah, some pharmacists are lazy-they don’t even read the scrip. I’ve seen ‘DAW 1’ scribbled in pencil and ignored. Meanwhile, the patient gets a new pill bottle and thinks nothing of it. This isn’t a medical debate-it’s a systemic failure of accountability. And don’t even get me started on how pharmacy benefit managers control everything. It’s a mess.

Sean Feng

January 15, 2026 AT 04:41Generic drugs are fine. End of story.

Priscilla Kraft

January 16, 2026 AT 14:50Thank you for writing this. 🙏 I’m a nurse in a rural clinic, and I’ve seen patients panic when their meds change-especially with warfarin or seizure drugs. We always check with the prescriber first, explain the switch, and schedule follow-up labs. It’s not about distrust-it’s about care. If we treat patients like data points, we fail. But if we treat them like people? We win. Let’s stop the fear-mongering and start the conversation.

Christian Basel

January 17, 2026 AT 22:19The therapeutic equivalence designation in the FDA’s Orange Book is based on pharmacokinetic parameters derived from healthy volunteers under fasting conditions. This does not account for inter-individual variability in absorption, distribution, metabolism, or excretion, particularly in polypharmacy populations with comorbidities like hepatic or renal impairment. Consequently, the assumption of bioequivalence translating to clinical equivalence is statistically valid but clinically reductive. The AAN’s position reflects a risk-averse clinical philosophy grounded in real-world outcomes data-not anti-generic sentiment. The issue is not the generic per se, but the lack of pharmacovigilance protocols surrounding substitution in high-risk populations.

Adewumi Gbotemi

January 18, 2026 AT 17:07Back home in Nigeria, we use generics because we have to. No one has insurance. If it works, we use it. But we also have community health workers who check in with patients weekly. Maybe the answer isn’t stopping generics-it’s having someone to watch over people when they switch. Simple care makes big difference.

Jennifer Littler

January 19, 2026 AT 22:54As someone who works in hospital pharmacy, I can confirm: the biggest risk isn’t the generic-it’s the lack of documentation. If a patient switches from brand to generic and no one updates the EHR or notifies the prescriber, of course bad things happen. We’ve implemented mandatory alerts for NTI drugs in our system. If the prescriber didn’t write DAW 1, the pharmacist has to call them. It’s extra work-but it saves lives. The system can work. We just need to fix the workflow, not blame the drug.