When a senior experiences chronic pain, the question isn’t just how to treat it - it’s how to treat it safely. Opioids can help, but they come with serious risks for people over 65. The old rules - like cutting doses in half or avoiding them entirely - didn’t work for everyone. Today, the approach is smarter, more personal, and grounded in real evidence.

Why Seniors Are Different

As we age, our bodies change in ways that affect how drugs work. The liver and kidneys don’t clear medications as quickly. Body fat increases, while muscle mass drops. This means opioids stay in the system longer, increasing the chance of side effects like dizziness, confusion, or breathing problems. Even small doses can be too much.Many seniors take five or more medications. Mixing opioids with sleep aids, antidepressants, or even over-the-counter pain relievers can be dangerous. One wrong combination can lead to delirium, falls, or worse. That’s why starting low and going slow isn’t just good advice - it’s a necessity.

What Opioids Are Safe - and Which to Avoid

Not all opioids are created equal for older adults. Some are safer than others, and some should be avoided entirely.Safe options include low-dose oxycodone, morphine, hydromorphone, and transdermal buprenorphine. Buprenorphine stands out because it’s a partial opioid agonist. Studies show it causes less constipation and fewer mental side effects than full agonists, even when used with small amounts of other opioids for breakthrough pain.

Medications to avoid include meperidine (Demerol), codeine, and methadone. Meperidine breaks down into a toxic compound that can trigger seizures and confusion - especially in seniors with kidney issues. Codeine is useless in many older adults because their bodies can’t convert it to morphine properly. Methadone builds up unpredictably and can cause dangerous heart rhythms.

Tramadol and tapentadol need caution too. They carry a risk of serotonin syndrome when mixed with SSRIs or SNRIs - common in seniors with depression or anxiety. And while they’re often used as "safer" alternatives, they’re not always more effective than traditional opioids.

Dosing: Start Low, Go Slow

For someone who has never taken opioids before, the starting dose should be 30% to 50% of what’s typically given to younger adults. That means:- 2.5 mg of oxycodone immediate-release (half a pill)

- 7.5 mg of morphine

- Or even lower if the patient is frail, over 80, or has liver or kidney disease

Never start with patches or long-acting pills like OxyContin or fentanyl patches. These deliver a steady stream of drug over hours - and if the body can’t process it, levels rise dangerously. Always begin with short-acting forms. Once the right dose is found, you can switch to extended-release versions - but only after the patient has been stable for weeks.

Don’t rush titration. Wait at least 48 hours between dose increases for short-acting opioids. For longer-acting ones, wait even longer. Pain relief shouldn’t be a race. It’s a careful climb.

What About Acetaminophen?

Many opioid prescriptions come with acetaminophen (Tylenol). But in seniors, this combo is risky. The maximum daily dose should be no more than 3,000 mg - and for frail seniors over 80, or those who drink alcohol regularly, it should be capped at 2,000 mg per day. Too much acetaminophen can cause liver failure, even without overdose. And because seniors often take multiple products that contain it - cold medicines, sleep aids, combination pain relievers - it’s easy to accidentally go over the limit.Non-Opioid Alternatives: Helpful, But Limited

Many doctors now turn to NSAIDs (like ibuprofen or naproxen) or gabapentinoids (like gabapentin or pregabalin) as "safer" options. But these aren’t perfect either.NSAIDs increase the risk of stomach bleeding, kidney damage, and heart failure in older adults. They should only be used for short bursts - no more than one or two weeks - during flare-ups.

Gabapentinoids were once seen as a solution for nerve pain. But a 2023 study in JAMA Network Open found they offer only a tiny reduction in pain - about 1 point on a 10-point scale - compared to placebo. Worse, they cause dizziness, confusion, and falls. For seniors already at risk for falling, that’s not a trade-off worth making.

Physical therapy, cognitive behavioral therapy, heat/cold therapy, and acupuncture have real benefits and should be part of every pain plan. But they rarely replace opioids entirely for moderate to severe pain, especially in cancer or advanced illness.

Monitoring: It’s Not Optional

Starting opioids is just the beginning. The real work is in watching how the patient responds.Every visit should include:

- Assessing pain levels and functional improvement - can they walk to the bathroom? Dress themselves?

- Checking for side effects: constipation, drowsiness, confusion, slowed breathing

- Evaluating fall risk - opioids increase this risk by 30% or more

- Reviewing all medications - including OTC and supplements

- Performing urine drug screens to confirm adherence and detect hidden substances

For anyone on opioids longer than three months, a written treatment agreement is required. It outlines goals, responsibilities, and consequences if rules are broken. This isn’t about distrust - it’s about safety.

Special Cases: Cancer Pain and End-of-Life Care

One of the biggest mistakes after the 2016 CDC guidelines was applying rigid dose limits to cancer patients. That’s changed. The 2022 CDC update explicitly says opioids remain the first-line treatment for moderate to severe cancer pain in seniors.Studies show about 75% of cancer patients respond well to opioids, with an average pain reduction of 50%. Denying them because of arbitrary dose caps leads to unnecessary suffering. The goal isn’t to eliminate all pain - it’s to let people live as fully as possible.

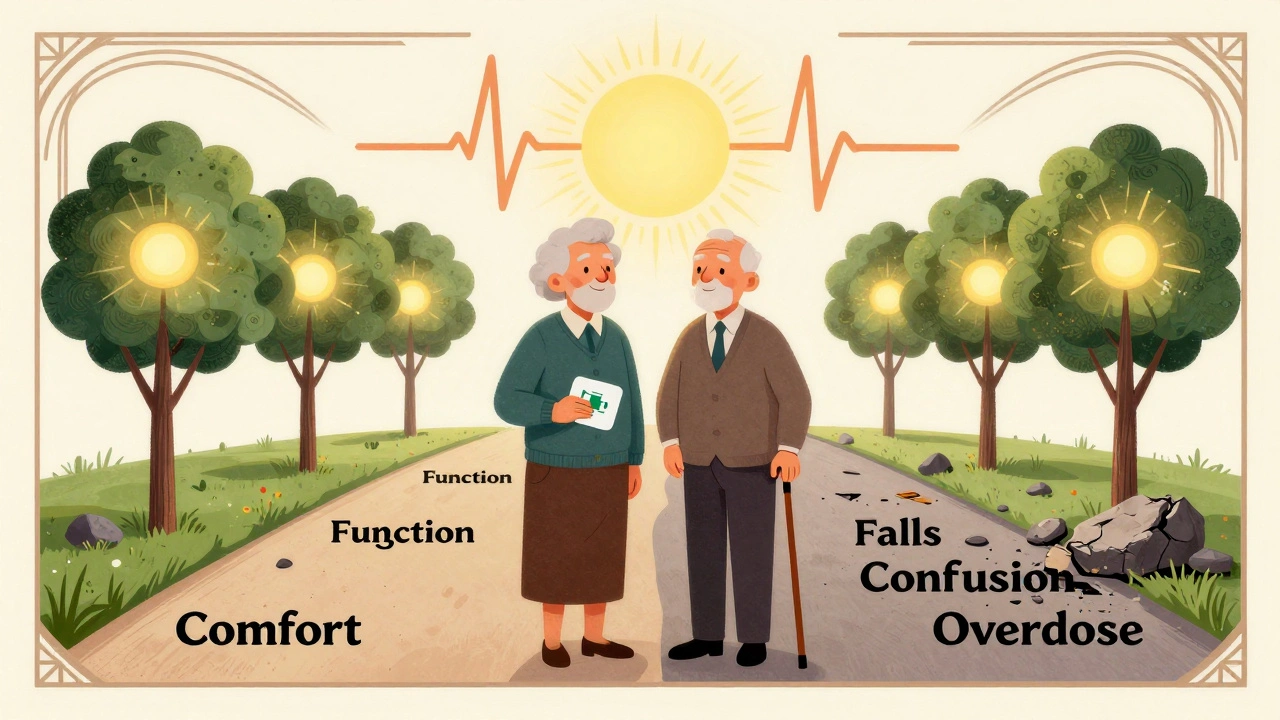

In end-of-life care, comfort is the priority. Dosing can be higher. The focus shifts from avoiding side effects to ensuring dignity and relief. Buprenorphine and morphine are commonly used here because they’re reliable and predictable.

The Bigger Picture: Individualization Is Key

There’s no one-size-fits-all plan. Two 75-year-olds with the same diagnosis may need completely different treatments. One might tolerate oxycodone well. Another might get dizzy from half a pill.That’s why guidelines now say: "Consider the benefits and risks in the context of the patient’s circumstances." It’s not about following a checklist. It’s about listening - to the patient, to their family, to their history.

Doctors who treat seniors know this. They watch for subtle signs: a slight tremor, a change in appetite, a new fall. They adjust doses based on how the person functions, not just how they score on a pain scale.

And they know when to stop. If opioids aren’t improving function - if the person is sleeping more, falling more, or seeming confused - it’s time to reassess. Sometimes, reducing or stopping opioids is the most compassionate choice.

What Comes Next?

The future of pain management in seniors is moving toward precision. Pharmacogenetic testing - checking how a person’s genes affect their response to drugs - is becoming more accessible. This could tell us if someone is likely to metabolize codeine poorly, or if they’re at higher risk for side effects from certain opioids.Non-drug options are expanding too. Nerve blocks, spinal cord stimulation, and targeted physical therapy are helping more seniors avoid opioids altogether. But for now, when pain is severe and persistent, opioids still have a vital role - if used wisely.

The key takeaway? Don’t fear opioids. Fear misusing them. With careful dosing, constant monitoring, and a focus on function - not just numbers - opioids can give seniors back their quality of life.

Are opioids ever safe for seniors with dementia?

Opioids can be used cautiously in seniors with dementia, but only if pain is clearly documented and other options have failed. Dementia patients can’t always report pain, so caregivers and clinicians must watch for non-verbal signs: grimacing, restlessness, refusal to move, or changes in sleep. Dosing must be even lower than usual, and monitoring must be frequent. The risk of confusion and falls is higher, so the benefits must clearly outweigh the risks.

Can opioids cause addiction in older adults?

Physical dependence is common with long-term opioid use - but true addiction (compulsive use despite harm) is rare in seniors. Most older adults take opioids as prescribed, especially when pain is real and ongoing. The bigger concern isn’t addiction - it’s side effects like falls, confusion, and breathing problems. Still, all opioid therapy should include regular reviews to ensure the medication is still needed and helping.

How often should seniors on opioids be checked?

Initial check-ins should happen every 1 to 2 weeks after starting or changing a dose. Once stable, visits can be every 1 to 3 months. Each visit must include a pain assessment, functional evaluation, side effect review, and medication reconciliation. Urine drug screens are recommended at least once a year, or more often if there’s concern about misuse or interactions.

What should I do if my senior loved one seems drowsy or confused on opioids?

Don’t wait. Call their doctor immediately. Drowsiness and confusion are red flags for opioid toxicity, especially in seniors. The dose may be too high, or there may be a dangerous interaction with another medication. Never stop the medication abruptly - that can cause withdrawal. But do not ignore these symptoms. They’re a signal that something needs to change.

Is buprenorphine really better for seniors?

Yes, for many seniors, buprenorphine is a better choice. It has a ceiling effect - meaning higher doses don’t increase side effects beyond a certain point. It causes less constipation and fewer cognitive issues than full opioids. Studies show it can be safely combined with low-dose oxycodone for breakthrough pain without triggering withdrawal. Transdermal patches are convenient, and the risk of respiratory depression is lower. It’s not perfect for everyone, but it’s often the safest option for long-term use.

Can seniors take opioids after surgery?

Yes, but with extra caution. Post-surgical pain is often severe, and opioids are effective. However, seniors need lower starting doses, shorter courses, and close monitoring. Avoid long-acting formulations. Use immediate-release options like oxycodone or hydromorphone in small doses. Combine with non-opioid pain relievers like acetaminophen (within safe limits) to reduce opioid needs. Most seniors can transition off opioids within a week or two with proper planning.

What to Do Next

If you’re caring for a senior with chronic pain:- Ask the doctor: "Is this the lowest effective dose?"

- Request a full medication review - including supplements and OTC drugs.

- Track changes in walking, sleeping, eating, and mood.

- Ask about non-drug options: physical therapy, heat therapy, or nerve blocks.

- Don’t assume pain is "just part of aging." It’s treatable - but only if it’s properly identified and managed.

Seniors deserve to live without unnecessary pain. But they also deserve to live without unnecessary risk. The balance is delicate - but with the right approach, it’s possible.

Jamie Clark

December 13, 2025 AT 08:47Opioids for seniors? More like a slow-motion suicide pact disguised as medicine. They say 'start low, go slow'-but who’s watching when the patient’s nodding off in the recliner? The system’s rigged. Pharma pushed this crap for decades, and now we’re told it’s 'safe' if you follow the checklist. Bullshit. The real checklist is: how many seniors died quietly while their kids were at work? No one’s auditing the corpses.

Keasha Trawick

December 13, 2025 AT 17:15OMG. I just read this like a medical thriller and I’m crying. 🫠 Buprenorphine as the quiet hero? YES. The way it glides in like a ninja-less constipation, less brain fog, no respiratory apocalypse? That’s the *dream*. And don’t even get me started on methadone-poison disguised as a solution. It’s like giving Grandma a time bomb wrapped in a prescription label. Meanwhile, acetaminophen? The silent assassin hiding in every cold med and sleep aid. We’re all just one Tylenol PM away from liver failure. 🚨

Ronan Lansbury

December 13, 2025 AT 22:19Let’s be honest: this entire framework is a performative charade orchestrated by the AMA and the CDC to appease the opioid litigation settlement fund. The 'evidence' cited? Mostly industry-funded trials with cherry-picked cohorts. Real clinical wisdom? It’s buried under 300 pages of bureaucratic jargon. And let’s not forget the real agenda: pushing seniors into physical therapy so insurers can save $2000 per patient. The truth? Opioids are the only honest option. The rest is just virtue signaling with a stethoscope.

Jennifer Taylor

December 15, 2025 AT 04:21MY GRANDPA TOOK OXYCONTIN FOR 8 YEARS AND HE’S STILL ALIVE BUT HE THINKS THE TV IS TALKING TO HIM 😭 I’M NOT KIDDING. HE ASKED ME IF THE NEWS ANCHOR WAS HIS DEAD WIFE. I CRIED. I JUST WANTED HIM TO WALK TO THE BATHROOM WITHOUT FALLING. NOW HE’S ON BUPRENORPHINE AND HE’S BACK TO WATCHING GAME OF THRONES AND ARGUING ABOUT DRAGONS. BUT I STILL CHECK HIS BREATHING EVERY NIGHT. I’M TERRIFIED. WHY DOESN’T THE DOCTOR JUST TELL US WHAT TO DO? 🤯

Shelby Ume

December 15, 2025 AT 05:17Thank you for writing this with such clarity and compassion. As a geriatric nurse, I’ve seen too many seniors suffer in silence because providers were afraid to prescribe-or worse, prescribed recklessly. The key is individualization. One 78-year-old with Parkinson’s and arthritis needs a different plan than another with COPD and a history of alcohol use. We must treat the person, not the diagnosis. And yes-urine screens aren’t about distrust. They’re about safety. Let’s normalize them. Let’s normalize care. Let’s stop treating pain like a moral failing.

Jade Hovet

December 15, 2025 AT 09:05YESSSSSS this is the info I needed!! 🙌 My mom’s on 2.5mg oxycodone and I was SO worried she’d turn into a zombie 😅 but she’s actually MORE alert now because her pain’s under control!! 🎉 Also-buprenorphine patch? GAME CHANGER. No more swallowing pills twice a day. And I finally learned how to check for constipation without sounding like a weirdo. 💩❤️🔥 Thank you for making me feel less alone!!

nithin Kuntumadugu

December 16, 2025 AT 14:54lol this whole article is just big pharma’s PR doc. buprenorphine? same shit, different label. they just renamed the poison. and ‘start low go slow’? yeah right. doctors don’t even know what a liver enzyme is. i saw a 79yo on 80mg morphine bc the doc ‘didn’t wanna upset the family.’ 😴 the system is broken. and acetaminophen? everyone’s overdosing on it like it’s candy. #opioidcrisis #pharmainc

John Fred

December 18, 2025 AT 09:01Big fan of the buprenorphine push here 🙌. I’ve been using it with my dad since last year-75, knee replacement, dementia, on 5 meds. We started at 1.5mg transdermal. No confusion. No constipation. He’s back to gardening. 🌱 That’s the win. And yes-monitoring is everything. We do a weekly ‘pain and function check’ over coffee. He tells me if he can get up without groaning. That’s the metric. Not the scale. Not the pill count. Just… is he living? 🤝